Image: Doughnuts. (Source: Pixabay, released under a CC0 creative commons license)

You are what you eat, as the old adage goes. But what if what we ate gave us cancer? It might sound like homeopathy, but increasing evidence suggests that our food does indeed have an impact on our risk of developing cancer, as well as our response to treatment.

Healthy eating reduces the risk of cancer

Attempting to determine what in our food is ‘healthy’ is no easy task, despite what health supplement companies may try to tell you.

There are so many different schools of opinion shouting for your attention – veganism (don’t eat meat), keto diet (don’t eat carbs), intermittent fasting (just don’t eat for a while) – it can seem overwhelming. And for every person who tells you it worked, you will find another who will say it was rubbish.

Research into nutrition and cancer is no less confusing. In 2013, researchers analysed studies on 50 common ingredients and charted their reported associations with cancer risk.

They found that for some foods such as caffeine you could find as many studies reporting an increased risk as those reporting a decrease. And individual studies often reported large effects that became more muted when the effects were combined across studies.

So are scientists lying to us – sensationalising their findings to sell us more coffee?

The answer is unfortunately much more boring. Controversial findings are often the result of poor study design. Trying to identify the effect of a single ingredient on cancer from a single study is like trying to find the average height of everyone in the UK by measuring the heights of a class of university students in Bath.

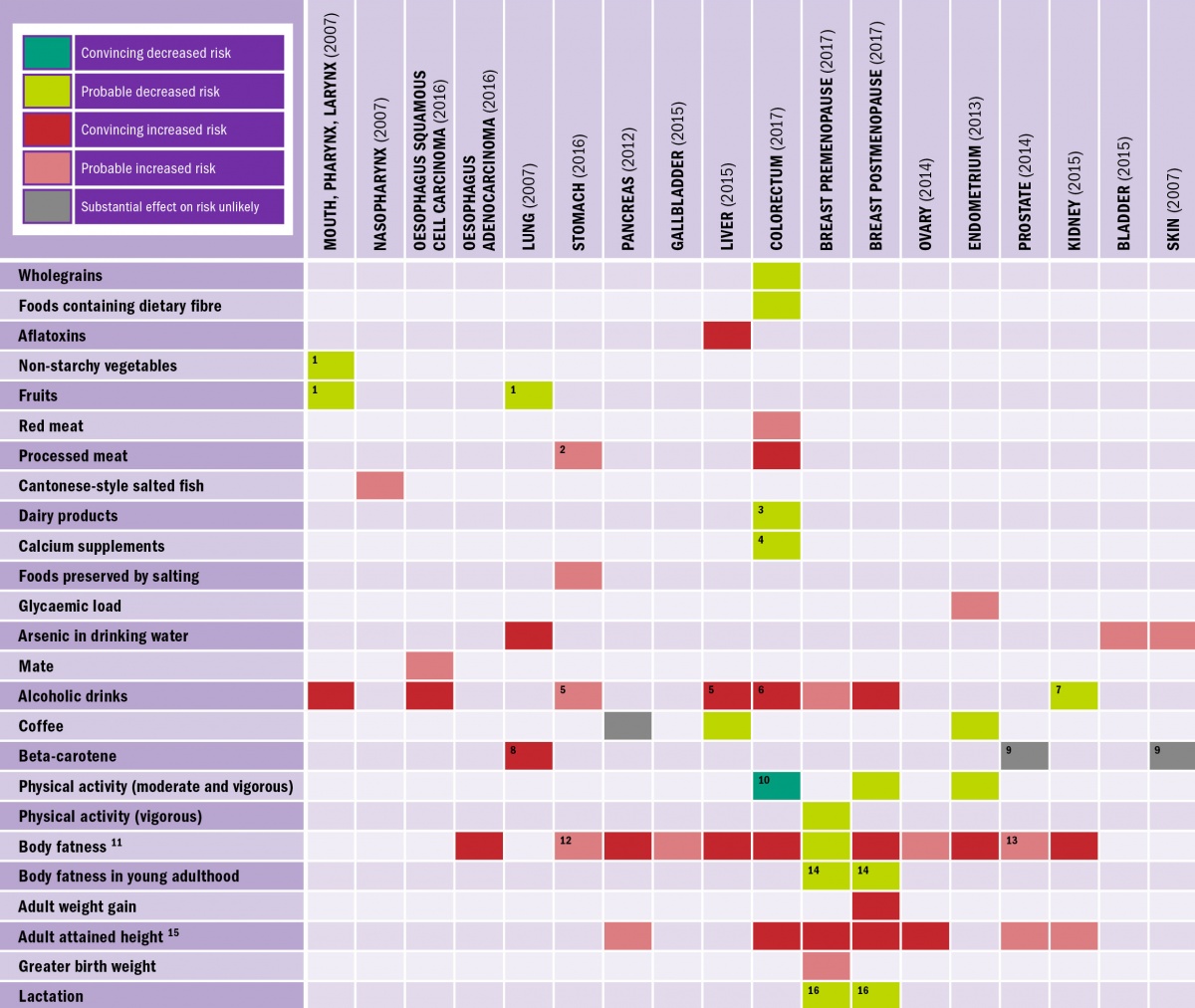

In order to get reliable data then, larger, more diverse and more representative sample sets are required. Enter global efforts like the World Cancer Research Fund International, which analyses large group studies in order to reliably identify foods that may be linked to cancer, with strong evidence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Evidence for diet and lifestyle factors in affecting the risk of cancer. Source: World Cancer Research Fund International

Unsurprisingly, ‘healthy’ diets high in fibre (from fruit and vegetables) and low in processed and preserved meats appear to lower cancer risk. Studies like this should help to guide us through the sea of fad diets to what exactly ‘healthy’ is.

Research at the ICR is underpinned by generous contributions from our supporters. Find out more about how you can contribute to our mission to make the discoveries to defeat cancer.

Find out more

What’s wrong with fat?

The biggest effect diet has on cancer risk is by increasing our body fat. A ‘healthy’ diet high in fruit and vegetables probably protects us at least in part by helping us to maintain a healthy weight. Since the 1930s, researchers have consistently found a correlation between ‘excessive nutrition’ and cancer.

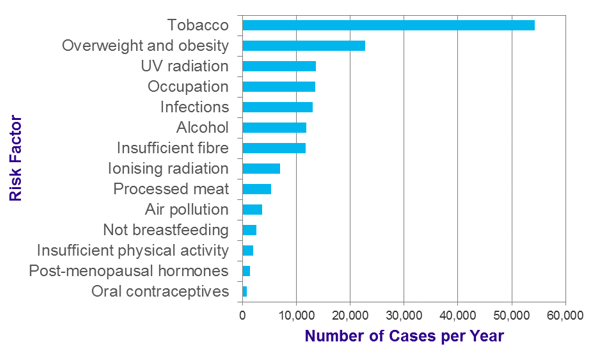

Obesity currently ranks just after tobacco as the leading cause of preventable cancers within the UK (see Figure 2) and has been linked to 11 different types of cancers.

Figure 2: Number of cancers per year ranked by causes. Source: Cancer Research UK (2015)

While rates of tobacco-related cancers have decreased with greater public awareness of the health risks, childhood and adult obesity are rising worldwide, sparking suggestions that obesity may, not too far in the future, overtake tobacco as the top contributor to cancer incidence.

It might feel like fat just sits there doing nothing, but it is actually really productive and important. Fat is an incredible source of energy and is important for cushioning our organs, but it also produces hormones and other factors that signal to the body.

This means that fat is not just involved in metabolism, but also growth signalling and immune function. Which is why too little or too much of it can have significant effects on our health.

Too much fat

Excess fat can lead to metabolic syndrome, a suite of chronic conditions including insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia (too much glucose in the blood). Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia lead to the increase of growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).

The body uses growth factors to signal to cells to grow, divide and survive – bad news if these cells turn out to be cancerous. People with diabetes have a higher risk of developing cancer, but doctors have noticed that patients on the drug metformin, which lowers blood glucose levels, had lower rates of cancer.

Today, metformin is being trialled as a cancer treatment alongside chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Fat itself produces plenty of pro-inflammatory factors that are linked to many cancers. In recognition of this, anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin or paracetamol are used with chemotherapy to improve some cancer treatments, especially in obese patients.

Fat also produces the hormone oestrogen, increasing the risk of developing breast cancer in post-menopausal women and men, who normally have little oestrogen. Besides this, fat also produces factors that promote blood-vessel formation, which cancer cells hijack to support survival within large tumours.

Tracking metabolism for better cancer detection and treatment

So bad nutrition can lead to too much fat, which increases our risk of cancer. But besides keeping track of our diet, how else can we use nutrition to fight cancer? Metabolomics - the study of biomarkers that indicate metabolic state or nutritional status - may be able to help.

Using metabolomics and machine learning to find patterns across patients, researchers have identified a specific metabolic profile that is as good at predicting breast cancer two to five years beforehand as a mammogram.

This could identify at-risk individuals before they notice any symptoms and give them access to increased screening. And the earlier a cancer is found, the easier it is to treat.

Metabolomics also provides a way to objectively study the effect of nutrition on the risk of cancer. Previous studies have relied largely on people reporting what they eat. Using metabolomics to analyse our metabolic profiles may finally help to nail down what chemicals in our food can help us in our fight against cancer.

Our nutritional status can also affect our response to therapy. Cancer cells acquire mutations that change their cellular ‘diet’ such that they become more dependent on certain compounds such as glucose, glutamate, glycine and serine.

Most recently, scientists identified that cancer cells also depend on the amino acid asparagine to spread, and that limiting it in the diet could stop cancer metastasis in animal models.

As we understand more about how our metabolism interacts with the metabolism of cancer cells, it opens up the possibility of patient-specific nutrition designed to complement traditional therapy. Who knows, one day we might even be able to treat cancer with exercise and diet, alongside traditional therapy.

Dr Maxine Lam is a Post-Doctoral Training Fellow in the Tumour Microenvironment Team in the Division of Cancer Biology.

comments powered by