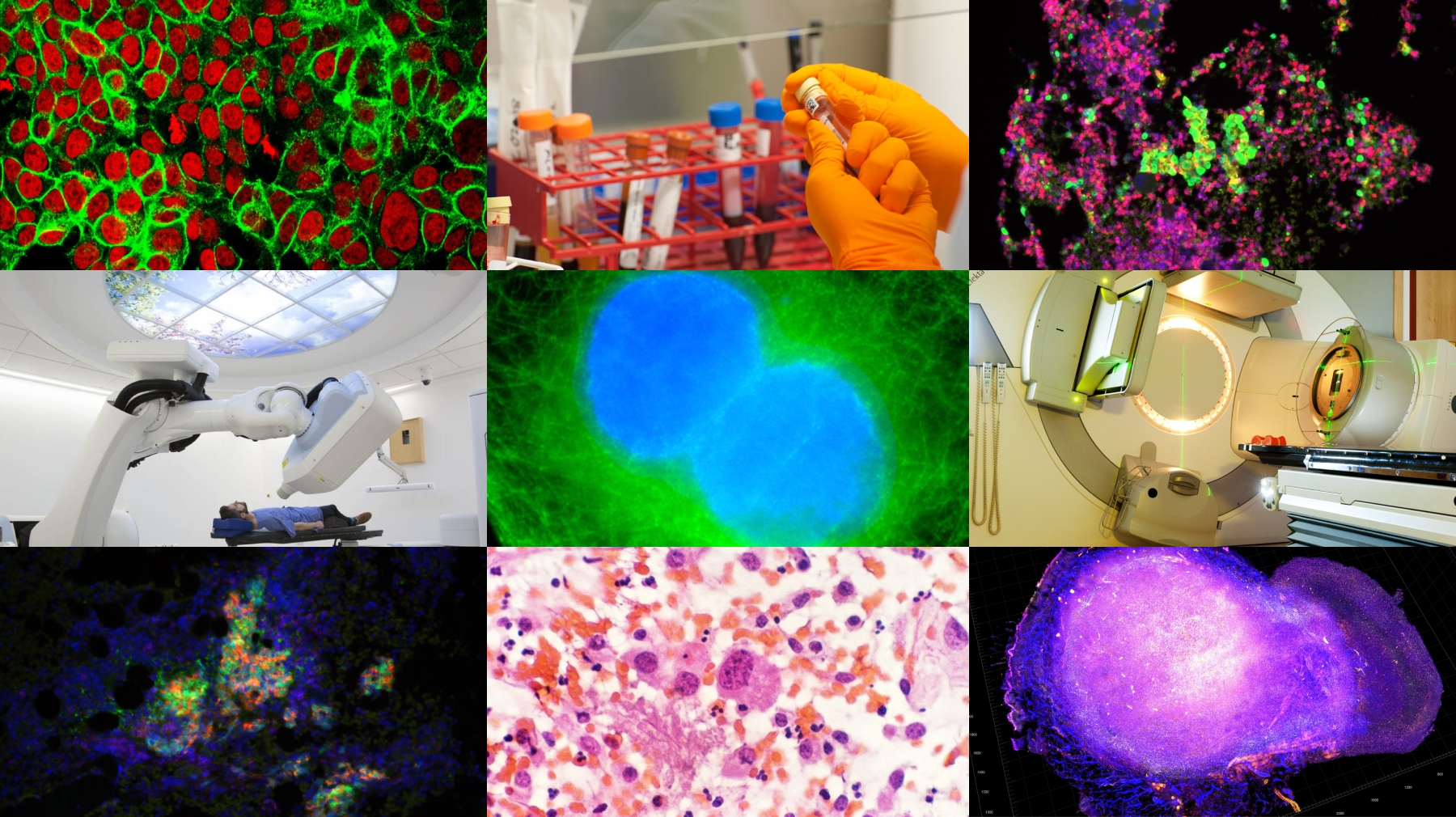

We've selected a range of discoveries from 2024/25 – chosen because they illustrate the quality and breadth of our basic, translational and clinical research and our ambitions under the ICR's research strategy.

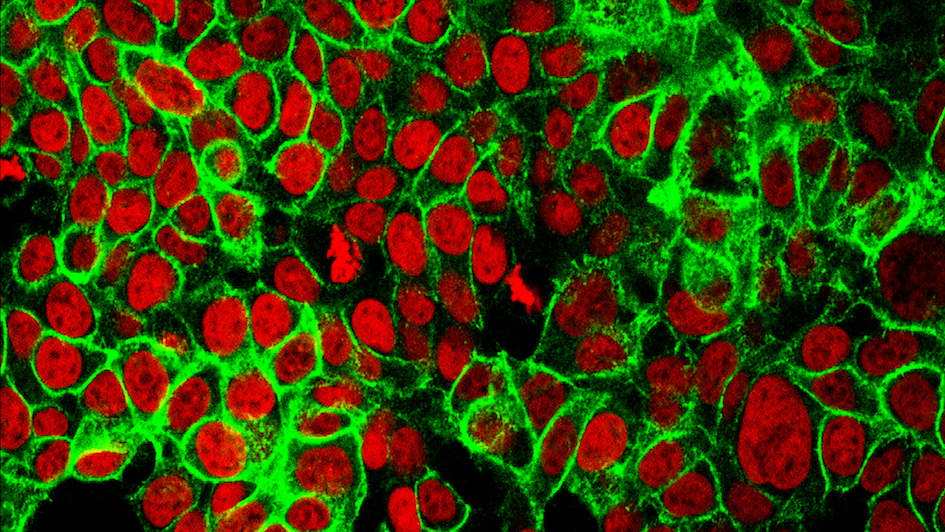

Uncovering a new role for a frequently mutated gene in cancer development

February 2025

945x532.png?sfvrsn=310c2acf_2)

Researchers have discovered a new protective role for a gene commonly mutated in cancer, offering a potential new therapeutic target. The study, led by Professor Jessica Downs, Deputy Head of the Division of Cell and Molecular Biology at the ICR, involved exploring how DNA is organised in the cell and its importance in maintaining the stability of the genetic material.

The researchers looked at how mutations in the PBRM1 gene – part of the PBAF chromatin remodelling complex – affect the centromere, a key region of DNA responsible for ensuring chromosomes separate accurately when a cell divides. The team found that loss of PBRM1 disrupts the structural integrity of the centromere, making it more fragile and prone to errors that can lead to cancer. By focusing on the instability caused by PBRM1 mutations, researchers hope to design drugs that selectively destroy cancer cells with damaged centromeres, while sparing healthy cells.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Karen A. Lane, Alison Harrod, Lillian Wu, Theodoros I. Roumeliotis, Hugang Feng, Shane Foo, Katheryn A. G. Begg, Federica Schiavoni, Noa Amin, Alan A. Melcher, Jyoti S. Choudhary and Jessica A. Downs

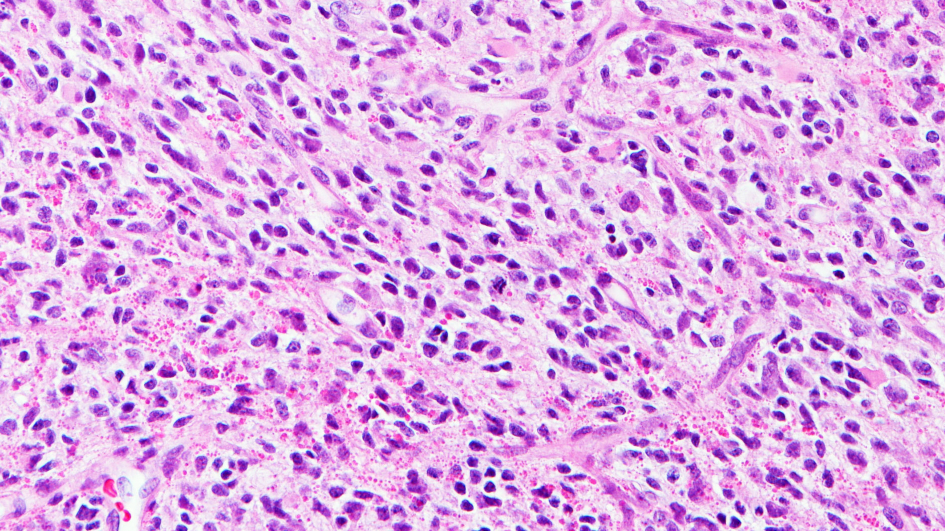

Potential new drug to target rare childhood brain tumour

August 2024

ICR researchers, led by Professor Chris Jones, in collaboration with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, have identified a promising new use for the breast cancer drug ribociclib – a CDK4/6 inhibitor – in treating a rare and aggressive childhood brain tumour called diffuse hemispheric glioma (DHG). This high-grade tumour, which accounts for more than 30 per cent of paediatric high-grade glioma diagnoses, currently has no cure and a typical prognosis of just 18–22 months. The study revealed that tumour cells disrupt normal neuronal development, making them resemble immature neuron-like cells. This insight led researchers to target a protein involved in cell division using ribociclib which showed potential in preclinical models.

In a compassionate-use case, ribociclib was administered to a child with DHG after other treatments failed, resulting in stable disease for 17 months – a significant extension given the usual rapid progression. While not a cure, the findings suggest that CDK4/6 inhibitors could form part of a combination therapy for this tumour type, which appears more responsive to these drugs than other gliomas. The research offers hope for future clinical trials and highlights the importance of understanding tumour biology to uncover new treatment strategies.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Lynn Bjerke, Rebecca F Rogers, Yura Grabovska, Alan Mackay, Valeria Molinari, Sara Temelso, Florence Raynaud, Ruth Ruddle, Fernando Carceller and Chris Jones

Mapping cancer vulnerabilities through synthetic lethality

March 2025

Groundbreaking research has uncovered how cancer cells adapt to harmful genetic changes by activating compensatory mechanisms, revealing new opportunities for targeted treatment. Led by Professor Chris Lord, Professor Andrew Tutt and Dr Syed Haider, the team studied more than 9,000 tumour samples and used drug screening to explore how the loss of tumour suppressor genes (TSGs) is compensated for by increased activity in other genes. This compensatory buffering allows cancer cells to survive despite genetic damage that would normally impair cell fitness.

The team developed a new analytical tool called SYLVER to identify these buffering relationships across 32 cancer types. They found that when key TSGs, such as BRCA1, are lost, cancer cells often ramp up expression of specific partner genes to compensate. These overactive genes form what the researchers call synthetic lethal metagenes – groups of genes that cancer cells rely on to survive when key protective genes are lost. Due to these metagenes being so important to cancer cell survival, they could be used as markers to detect cancer or as targets for new treatments. The study provides strong evidence that these gene relationships, previously seen in lab experiments, are present in real human cancers too – paving the way for more precise and effective treatments that exploit these hidden vulnerabilities.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Syed Haider, Rachel Brough, Santiago Madera, Jacopo Iacovacci, Aditi Gulati, Andrew Wicks, John Alexander, Stephen J. Pettitt, Andrew N. J. Tutt and Christopher J. Lord

A simple spit test could revolutionise prostate cancer screening

April 2025

.jpg?sfvrsn=d0c8e3d2_1)

A new saliva-based genetic test could transform how prostate cancer is detected, offering a simpler and more accurate alternative to current screening methods. Developed through the BARCODE 1 study, the test calculates a polygenic risk score from DNA in saliva to identify men at highest genetic risk. Unlike the standard PSA blood test, this approach was better at spotting aggressive cancers and even detected cases missed by MRI scans and those with normal PSA levels.

In a trial involving more than 6,000 men aged 55–69, those in the top 10 per cent of genetic risk were invited for further screening. Of these men, 40 per cent were diagnosed with prostate cancer, with more than half of cases being aggressive.

Building on these findings, researchers, led by Professor Ros Eeles, Professor of Oncogenetics at the ICR and Consultant in Clinical Oncology and Cancer Genetics at The Royal Marsden, have created an enhanced version of the test, PRODICT®, which includes a broader range of genetic variants and is suitable for more diverse populations. It is now being trialled in the large-scale TRANSFORM study, which aims to compare its effectiveness with PSA and MRI screening. If successful, this simple spit test could save thousands of lives and significantly reduce NHS costs.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Jana K McHugh, Elizabeth K Bancroft, Edward Saunders, Mark N Brook, Eva McGrowder, Sarah Wakerell, Denzil James, Reshma Rageevakumar, Barbara Benton, Natalie Taylor, Kathryn Myhill, Matthew Hogben, Elizabeth C Page, Andrea Osborne, Sarah Benafif, Ann-Britt Jones, Questa Karlsson, Tokhir Dadaev, Sibel Saya, Susan Merson, Angela Wood, Nening Dennis, Nafisa Hussain, Alison Thwaites, Syed Hussain, Nicholas D James, Zsofia Kote-Jarai and Rosalind A Eeles

Scientists develop new tool to beat cancer’s survival tactics

August 2024

A major international study, which included researchers at the ICR, has uncovered more than 250 genes linked to bowel cancer – many of which had never previously been associated with the disease. Using whole-genome data from more than 2,000 samples from colorectal cancer patients collected through the 100,000 Genomes Project, the team identified new genetic faults and classified colorectal cancer into distinct sub-groups based on its genetic features. These sub-groups differ in how they behave and respond to treatment, offering new insights into the disease’s complexity.

The study, published in Nature, also revealed that genetic changes vary across different regions of the bowel and between individuals, with some mutations more common in younger patients – potentially influenced by lifestyle factors like diet and smoking. Importantly, many of the newly identified mutations could be targeted using existing drugs already approved for other cancers.

Co-lead researcher Professor Richard Houlston, Professor of Cancer Genomics, said the findings offer a powerful foundation for developing personalised treatments tailored to the genetic makeup of each patient’s cancer. The research also opens the door to exploring the role of the gut microbiome in bowel cancer development, which could further improve outcomes in the future.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Alex J. Cornish, Ben Kinnersley, Daniel Chubb, Giulio Caravagna, Eszter Lakatos, Jacob Househam, William Cross, Amit Sud, Philip Law, Luis Zapata, Trevor A. Graham and Richard S. Houlston

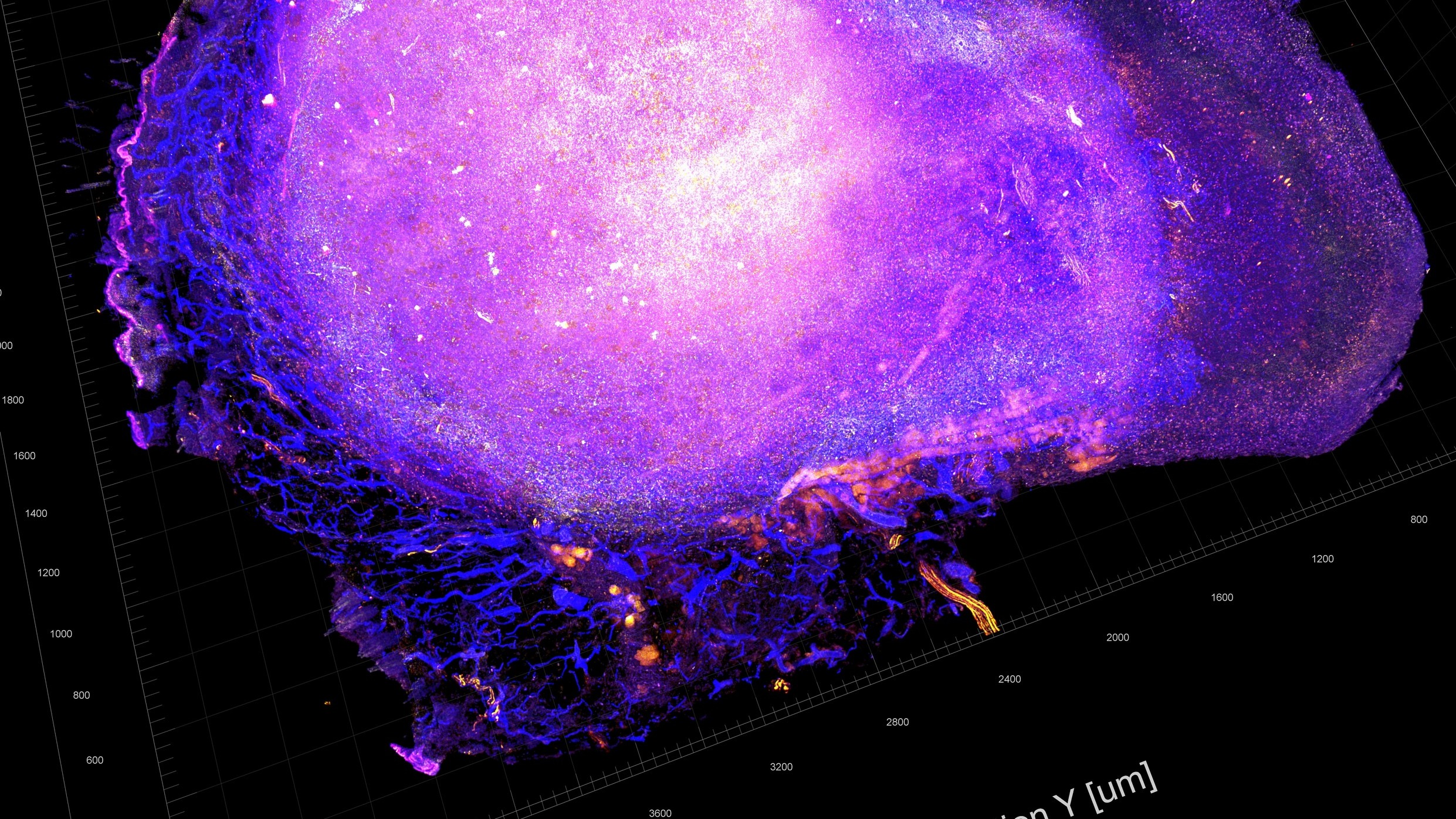

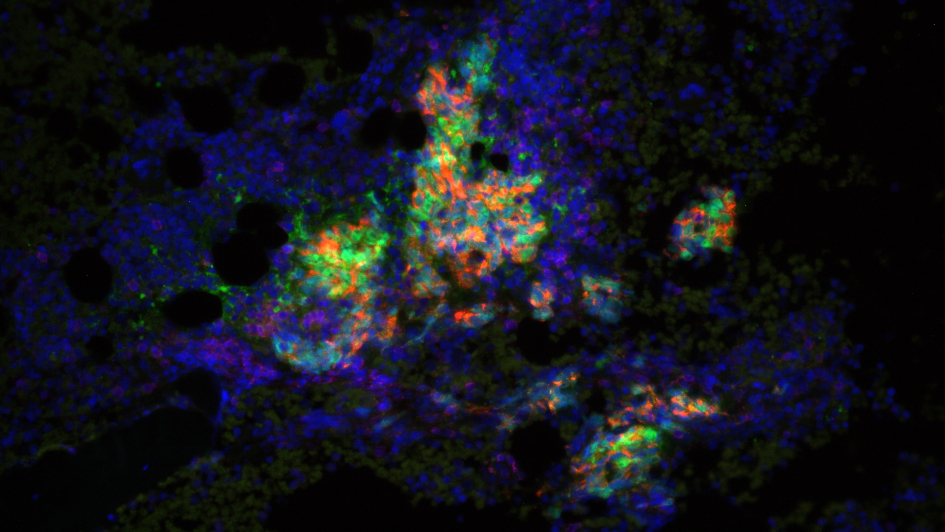

Harnessing stress signals to improve immune detection of cancer

May 2025

An innovative study has discovered how combining a targeted cancer drug with a cancer-killing virus can make tumours more visible to the immune system, potentially aiding earlier and more precise diagnosis. The study, led by Professor Kevin Harrington, Professor in Biological Cancer Therapies at the ICR and Consultant Oncologist at The Royal Marsden, explored the effects of palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, used alongside an oncolytic virus that selectively infects and kills cancer cells. Together, these agents triggered strong stress responses inside tumour cells, leading to increased production of interferons and activation of immune pathways that help the body detect and respond to cancer.

Importantly, the combination therapy altered how tumour cells present antigens – the molecular flags that alert the immune system – by increasing the display of immune-recognition proteins on the surface of cancer cells and activating hidden viral-like signals within them that help alert the immune system. These changes made cancer cells more visible to immune cells and increased the likelihood of immune attack.

The findings suggest that this approach could not only improve treatment outcomes but also reveal ways to detect the presence of cancer earlier or indicate when a tumour is becoming resistant to therapy.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Victoria Roulstone, Joan Kyula-Currie, James Wright, Emmanuel C. Patin, Isaac Dean, Lu Yu, Aida Barreiro-Alonso, Miriam Melake, Jyoti Choudhary, Richard Elliott, Christopher J. Lord, David Mansfield, Nik Matthews, Ritika Chauhan, Victoria Jennings, Charleen Chan Wah Hak, Holly Baldock, Francesca Butera, Elizabeth Appleton, Pablo Nenclares, Malin Pedersen, Shane Foo, Amarin Wongariyapak, Antonio Rullan, Tencho Tenev, Pascal Meier, Alan Melcher, Martin McLaughlin and Kevin J. Harrington

Targeting breast cancer in its earliest stages

June 2025

A major international study has shown that a next-generation drug called inavolisib could significantly improve outcomes for patients with advanced breast cancer. The treatment targets mutations in the PIK3CA gene, which are found in around 40 per cent of hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancers. These mutations help cancer cells grow and resist treatment. When inavolisib was combined with palbociclib and hormone therapy, it delayed the need for chemotherapy by nearly two years compared with standard treatment, and patients lived longer.

The study, where Professor Nick Turner, Professor of Molecular Oncology at the ICR and Director of Clinical Research at The Royal Marsden, was co-principal investigator, also demonstrated the power of personalised medicine, using a blood-based ‘liquid biopsy’ tests to identify patients with the PIK3CA mutation.

This approach not only guided treatment decisions but also highlighted how molecular diagnostics can support earlier and more precise cancer detection. The findings build on more than two decades of collaborative research between ICR's Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery and industry partners into PI3K inhibitors – a journey that began in the late 1990s and led to the development of some of the first drugs targeting this pathway. This long-standing expertise helped lay the groundwork for inavolisib and reflects a broader shift toward tailoring cancer treatments based on genetic insights, enabling earlier and more precise intervention.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Nicholas C. Turner

Predicting how long prostate cancer patients will benefit from targeted treatment

December 2024

New research has shown that it’s possible to predict how long men with advanced prostate cancer will respond to the targeted drug olaparib, based on specific genetic markers in their tumours. The study focused on patients with metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer who had stopped responding to standard treatments. By analysing tumour samples using next-generation sequencing, researchers identified defects in DNA-repair genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM and CHEK2 – mutations that make cancer cells more vulnerable to PARP inhibitors like olaparib.

The study, led by Professor Johann de Bono, Regius Professor of Cancer Research at the ICR and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden, revealed that patients with these mutations were far more likely to benefit from olaparib, with 88 per cent of those carrying BRCA2 or ATM alterations responding to treatment.

This genetic insight not only helps guide personalised treatment decisions but also allows clinicians to estimate how long a patient is likely to benefit from the drug. By identifying these genetic mutations early, clinicians can better tailor therapies and avoid unnecessary treatments, supporting more precise and effective cancer care.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: George Seed, Nick Beije, Wei Yuan, Claudia Bertan, Jane Goodall, Arian Lundberg, Matthew Tyler, Ines Figueiredo, Rita Pereira, Chloe Baker, Denisa Bogdan, Lewis Gallagher, Maryou Lambros, Lorena Magraner-Pardo, Gemma Fowler, Berni Ebbs, Susana Miranda, Penny Flohr, Pasquale Rescigno, Nuria Porta, Emma Hall, Bora Gurel, Adam Sharp, Stephen Pettit, Christopher J Lord, Suzanne Carreira and Johann de Bono

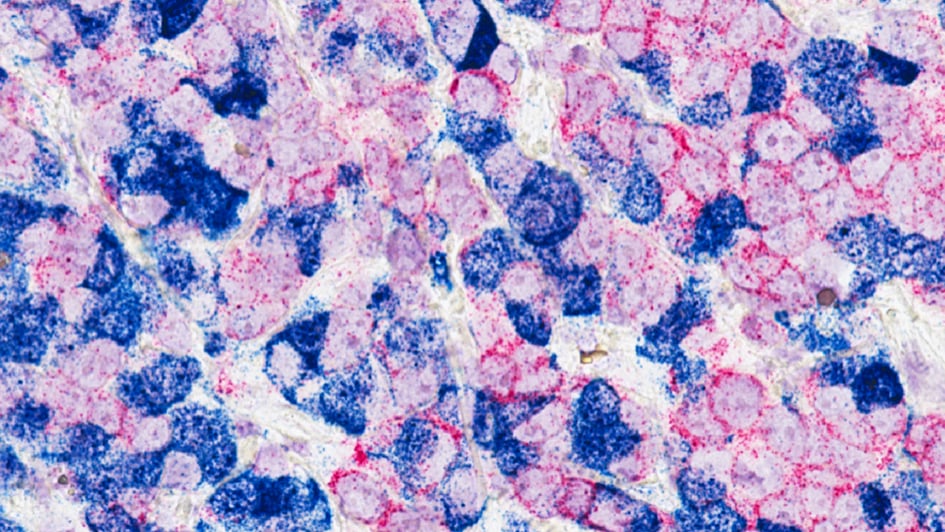

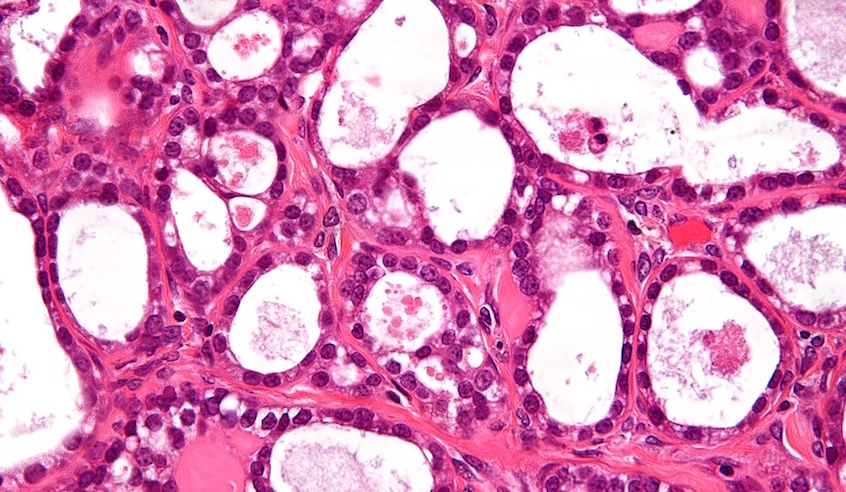

How genetic changes affect treatment response in myeloma

May 2025

.jpg?sfvrsn=eb2d940b_1)

Research led by Dr Charlotte Pawlyn, Group Leader of the Myeloma Biology and Therapeutics Group in the Division of Cancer Therapeutics, has discovered how specific changes in a gene called CRBN can influence how well patients with multiple myeloma respond to certain treatments. These treatments, known as immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), are commonly used to manage the disease, but some patients eventually stop responding. The study found that nearly one third of patients who became resistant to one of these drugs had developed mutations in the CRBN gene – a key part of how these drugs work.

To understand the impact of these mutations, the research team recreated them in the lab and found that some mutations completely blocked the drug’s effect, others had no impact, and some caused resistance to IMiDs but still allowed newer treatments to work. This means that even if a patient’s cancer stops responding to older drugs, they may still benefit from newer ones. The findings could help clinicians use genetic testing to guide treatment decisions more accurately and offer more personalised care for those with myeloma.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Yakinthi Chrisochoidou, Andrea Scarpino, Salomon Morales, Shannon Martin, Sarah Bird, Yigen Li, Brian Walker, John Caldwell, Yann-Vaï Le Bihan, Charlotte Pawlyn

New drug combination approved for rare ovarian cancer

June 2025

A new combination of targeted drugs has been approved in the US for treating a rare form of ovarian cancer, marking a major milestone for patients with recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC). The treatment combines avutometinib and defactinib and was developed through a long-standing collaboration between the ICR, The Royal Marsden and Verastem Oncology. The approval by the FDA is the first worldwide for any treatment specifically for recurrent LGSOC, which is often resistant to chemotherapy and hormone therapy.

The decision was based on positive results from the RAMP 201 trial, co-led by Professor Susana Banerjee, Consultant Medical Oncologist and Research Lead for the Gynaecology Unit at The Royal Marsden and Professor in Women’s Cancers at the ICR.

The trial followed earlier research, led by Professor Udai Banerji, Co-Director of Drug Development at the ICR and The Royal Marsden, which discovered an innovative, less toxic way to use the drug combination to target cancers driven by certain mutations. These mutations are notoriously difficult to treat, but the new therapy offers a more effective and better-tolerated option for patients.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Susana Banerjee, Alastair Greystoke, Alvaro Ingles Garces, Vicky Sanchez Perez, Angelika Terbuch, Rajiv Shinde, Reece Caldwell, Rafael Grochot, Mahtab Rouhifard, Ruth Ruddle, Bora Gurel, Karen Swales, Nina Tunariu, Toby Prout, Mona Parmar, Stefan Symeonides, Jan Rekowski, Christina Yap, Adam Sharp, Alec Paschalis, Juanita Lopez, Anna Minchom, Johann Sebastian de Bono and Udai Banerji

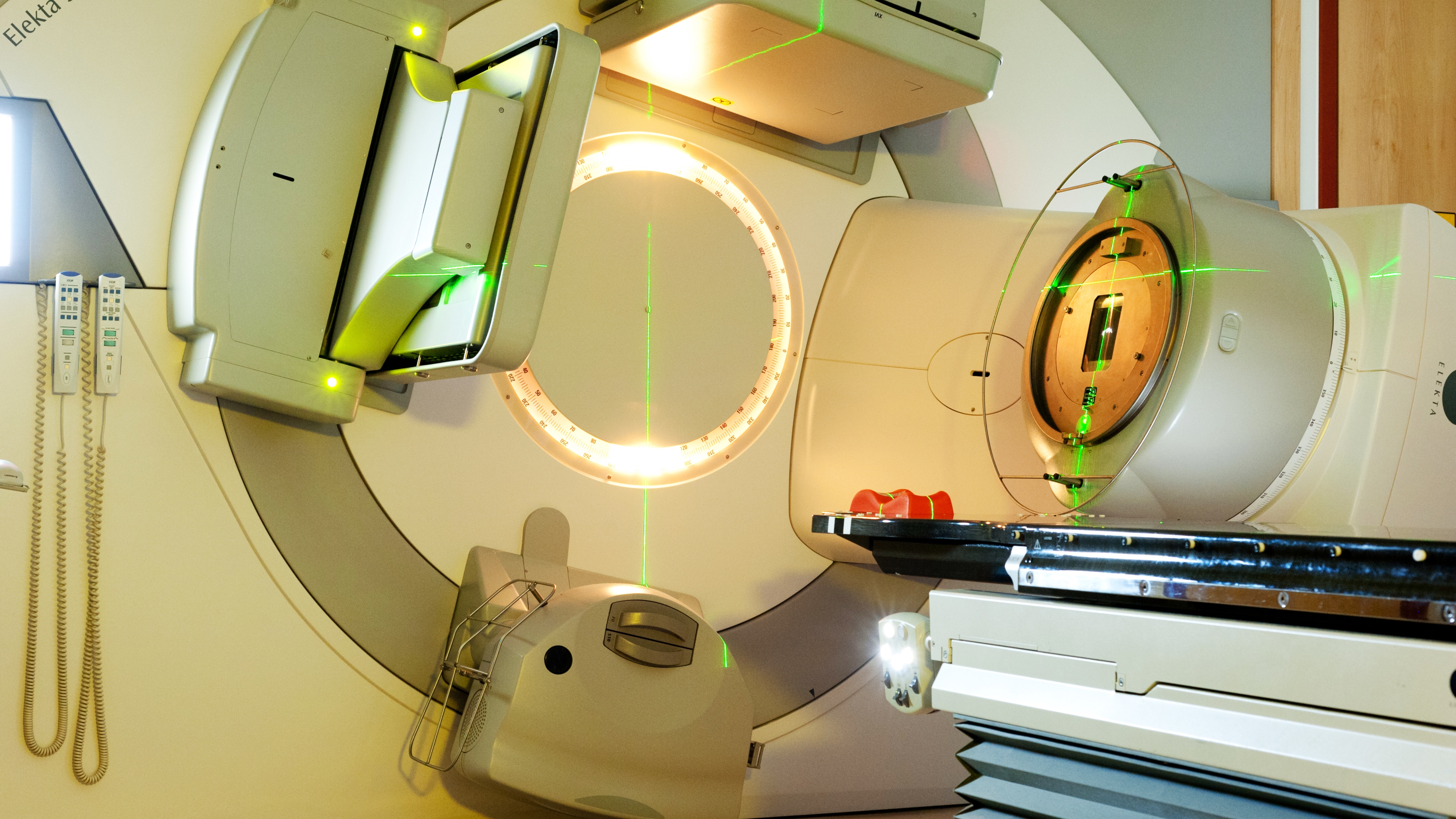

More personalised radiotherapy offers same protection with fewer side effects

July 2025

A major UK trial has shown that women with low-risk breast cancer can receive more targeted radiotherapy without effectiveness being compromised. The IMPORT LOW trial, co-led by Professor Judith Bliss, Founding Director of the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the ICR, found that limiting radiation to the area around the tumour is just as effective as treating the whole breast. After ten years of follow-up, recurrence rates were just 3 per cent – the same as with traditional whole-breast radiotherapy.

The more targeted approach, known as partial-breast radiotherapy, significantly reduced long-term side effects such as changes in breast appearance, swelling and pain. It has now been widely adopted across the NHS and internationally, with around 9,000 women in the UK expected to benefit each year. Tailoring treatment based on individual risk can improve quality of life without compromising outcomes – a key step forward in making cancer care more precise and patient-centred.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Anna M Kirby, Laura Finneran, Clare L Griffin, Fay H Cafferty, Joanne S Haviland, Mark A Sydenham, John R Yarnold and Judith M Bliss

Precision radiotherapy cuts treatment time without compromising outcomes

October 2024

Professor Nicholas van As, Medical Director and Consultant Clinical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden and Professor in Precision Prostate Radiotherapy at the ICR, was chief investigator of a major clinical trial that has shown that men with intermediate-risk, localised prostate cancer can receive effective treatment in just five sessions of radiotherapy, instead of the usual 20. The PACE-B trial, led by Professor van As and the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the ICR with Professor Emma Hall as the study's academic lead found that stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) – which delivers higher doses with pinpoint accuracy – was just as effective as conventional radiotherapy. After five years, 96 per cent of patients treated with SBRT remained free of signs of cancer recurrence, compared with 95 per cent of those with standard treatment.

SBRT uses advanced imaging and robotic technology to track and target tumours with sub-millimetre precision, reducing damage to surrounding healthy tissue. While side effects were slightly more common in the SBRT group, they remained low overall and comparable to conventional treatment. The findings are expected to change clinical practice, offering patients a quicker, more convenient option without compromising outcomes.

ICR researchers involved in this achievement: Nicholas van As, Clare Griffin, Alison Tree, Jaymini Patel, Emily Williamson, Julia Pugh, Georgina Manning, Stephanie Brown, Stephanie Burnett and Emma Hall