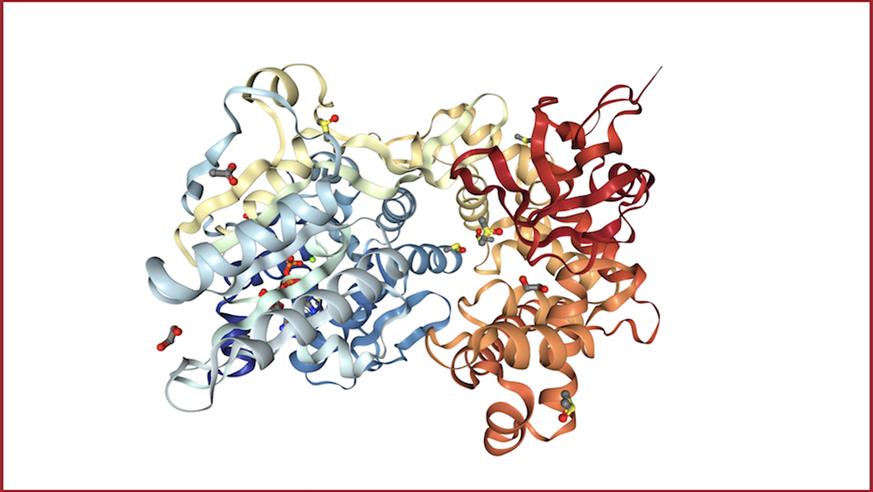

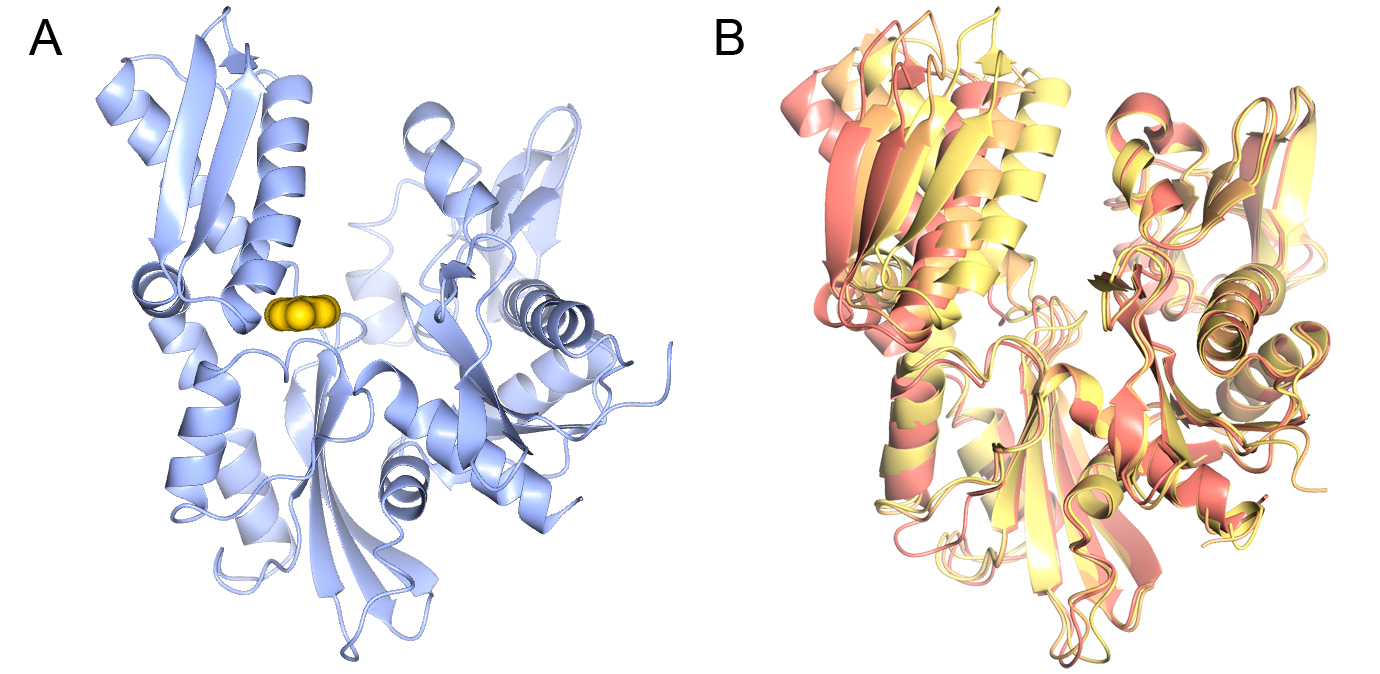

Image: Crystal structure of DHX8 helicase domain bound to ADP. PDB ID: 6HYS. Credit: Felisberto-Rodrigues et al., 2019, NGL viewer and RCSB PDB.

Scientists have revealed close-up details of a vital molecule involved in the mix and match of genetic information within cells – opening up the potential to target proteins of this family to combat cancer’s diversity and evolution.

A team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, has discovered the three-dimensional structure and function of this ‘mix n match’ protein, which helps control a process linked to cancer’s progression and drug resistance.

The researchers believe the study opens up a potentially exciting new way to tackle drug-resistant cancers and will be exploring the possibility further within the pioneering £75 million new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery.

The study is published in Biochemical Journal today (14th September) and was funded by Cancer Research UK with additional support from the Faringdon Fund, which was created by The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) to get high-risk projects off the ground following a generous philanthropic donation.

We now have less than £14m to raise to build The Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery. To make our building a reality, we urgently need your philanthropic support.

Alternative splicing: a fundamental process

Researchers at the ICR investigated the structure and function of a molecule known as DHX8. This belongs to a class of proteins involved in a fundamental process in life called ‘alternative splicing’, which affects 95 per cent of human genes.

Splicing takes place once the DNA code has been copied into RNA, with certain pieces cut out and the rest stuck together to create a final code that is translated into protein.

In alternative splicing, the bits of RNA that are cut out, or kept in, can be varied to create multiple proteins from a single gene – increasing the diversity of proteins available to cells.

When alternative splicing goes wrong, it can generate changes to the proteins within cells – which can lead to cancer, or fuel cancer’s diversity, evolution and drug resistance.

Splicing is carried out by a complex made up of proteins and RNA, which constantly changes during the cutting and gluing of RNA. DHX8 is a crucial member of this complex and helps to release the finished RNA into the cell so it can be translated into protein.

Visualising the molecular structure

In this new study, the researchers examined how the human DHX8 protein binds to RNA and acts to unravel RNA from the rest of the splicing machinery.

They also determined the first high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of DHX8 with and without RNA – allowing them not only to visualise the protein’s molecular structure but also to gain key clues about its function.

In particular, the study shed light on the roles of specific structural regions of DHX8, including the so-called ‘DEAH motif’, ’hook loop’ and ‘hook turn’ regions, which were all shown to be vital for DHX8’s function.

The researchers next want to study in greater detail how DHX8 can contribute to cancer – and believe their study will open up ways of blocking members of the protein family as a promising new approach to treatment.

Tackling cancer evolution and drug resistance

Attempting to combat cancer’s diversity is one of the central strategies the ICR is pursuing as part of a pioneering research programme to overcome the ability of cancers to adapt, evolve and become drug resistant.

The ICR – a charity and research institute – is raising the final £14 million of a £75 million investment in the new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery to house a world-first programme of ‘anti-evolution’ therapies.

Study leader Dr Rob van Montfort, Team Leader in Hit Discovery and Structural Design at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“Our study has shed new light on the structure and function of a crucial protein involved in the process of alternative splicing, in which genetic information is mixed and matched to create multiple protein molecules from a single gene.

“Cancer cells take advantage of alternative splicing to diversify, evolve and escape the body’s regulatory mechanisms. By determining the detailed molecular structure of one of the key protein molecules involved in alternative splicing, we have opened up potentially exciting new avenues for cancer treatment.”

Opening 'a new route' to block cancer's evolution

Study co-author Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“We are excited to study these ‘mix and match’ proteins further, because we think our findings open up a new route to help block cancer’s evolutionary pathways, and potentially overcome drug resistance.

“This is exactly the sort of approach we plan to take within our pioneering new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery, which once completed will house the world’s first ‘Darwinian’ drug discovery programmed dedicated to overcoming the twin challenges of cancer evolution and drug resistance.”

Dr Emily Farthing, research information manager at Cancer Research UK, said:

“This research provides valuable information about how cancer cells hijack a process in our cells to make them more diverse and enables them to evade treatment. Although more work is needed to build on these findings, this research could open up the possibility of novel cancer therapies in the future.”

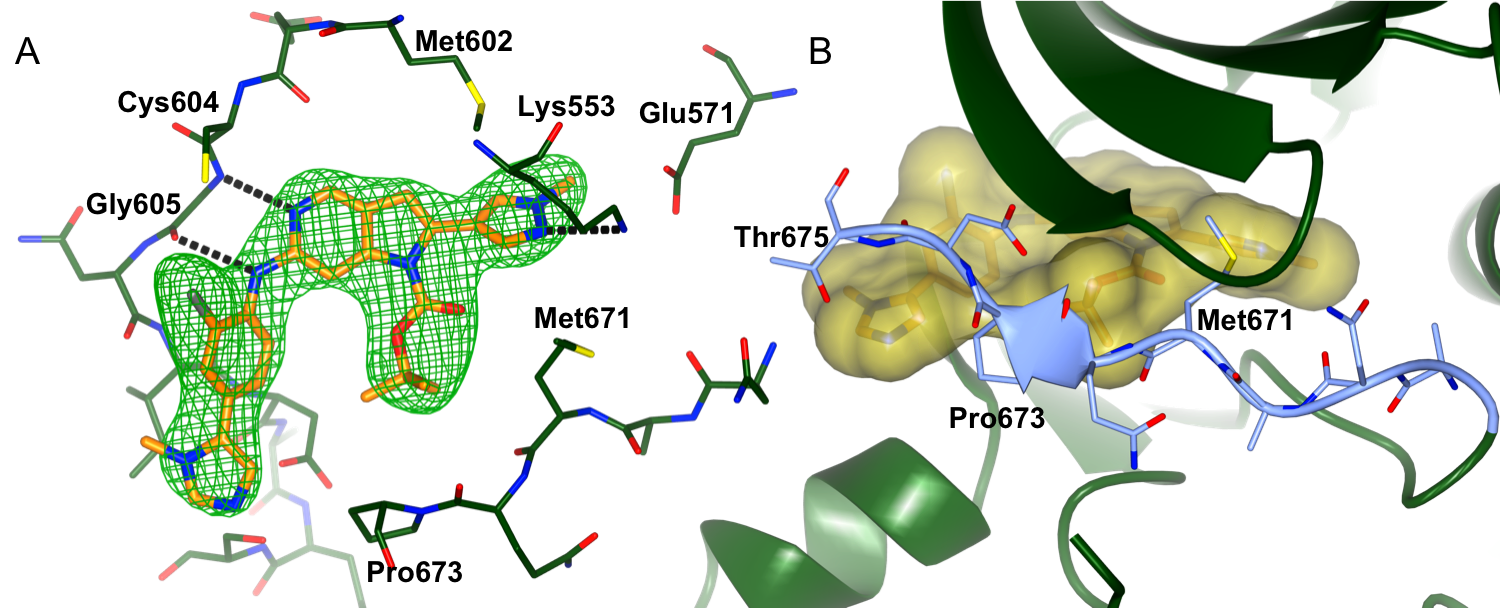

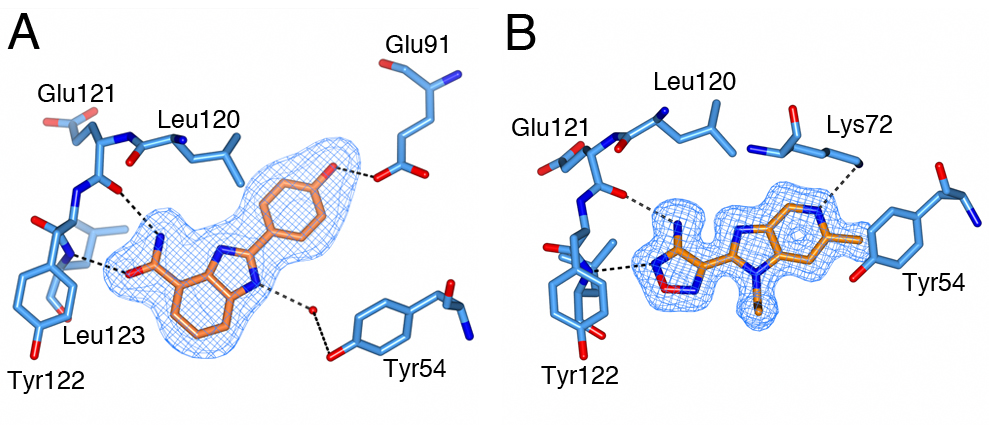

Figure 1: Binding of CCT251455 to MPS1. (A) Binding of CCT251455 to the hinge region of MPS1. (B) CCT251455 stabilises and unusual conformation of the activation loop (light blue).

Figure 1: Binding of CCT251455 to MPS1. (A) Binding of CCT251455 to the hinge region of MPS1. (B) CCT251455 stabilises and unusual conformation of the activation loop (light blue). Figure 2: Binding of KDM4/5 inhibitors to KDM4A. A) Superposition of two KDM4/5 inhibitors (blue/organge) bound to KDM4A highlighting key interactions with the protein. B) 2D interaction diagram showing the interactions of the most potent inhibitor (orange) with KDM4A.

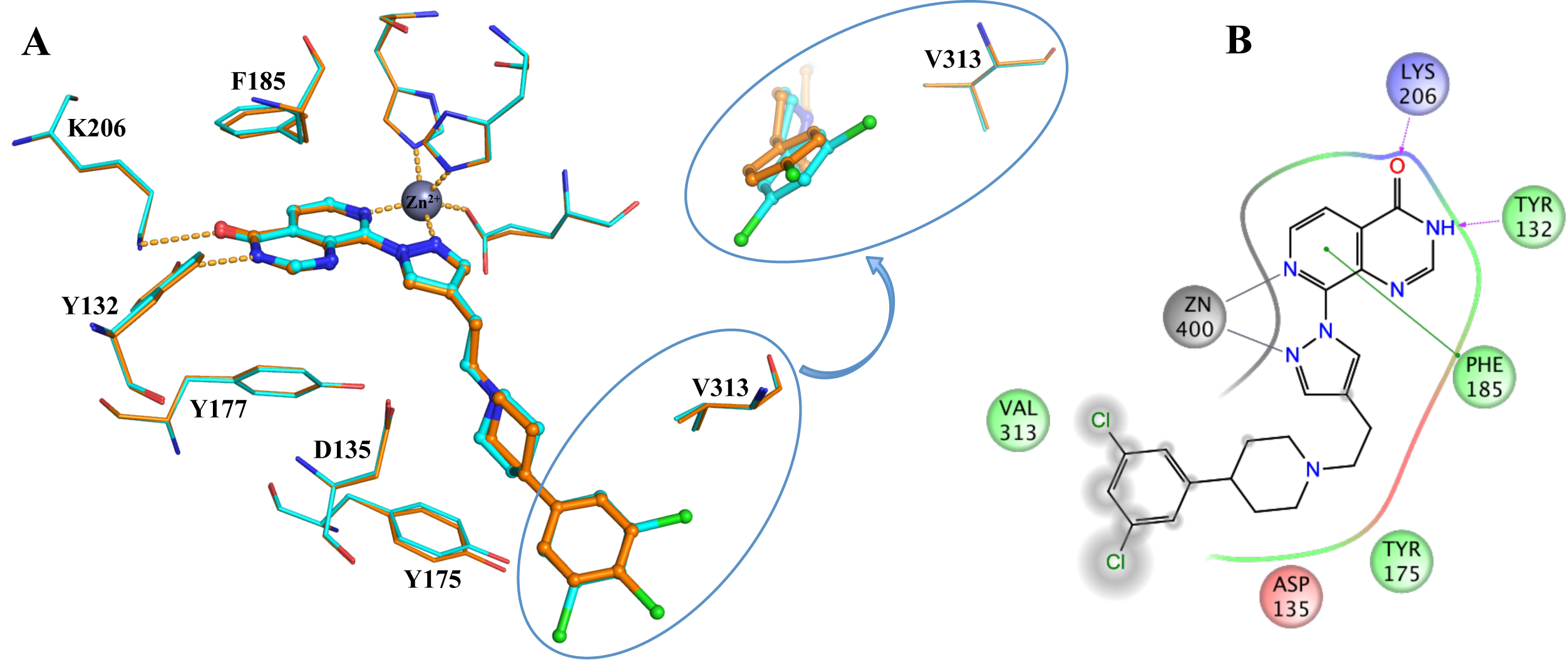

Figure 2: Binding of KDM4/5 inhibitors to KDM4A. A) Superposition of two KDM4/5 inhibitors (blue/organge) bound to KDM4A highlighting key interactions with the protein. B) 2D interaction diagram showing the interactions of the most potent inhibitor (orange) with KDM4A.

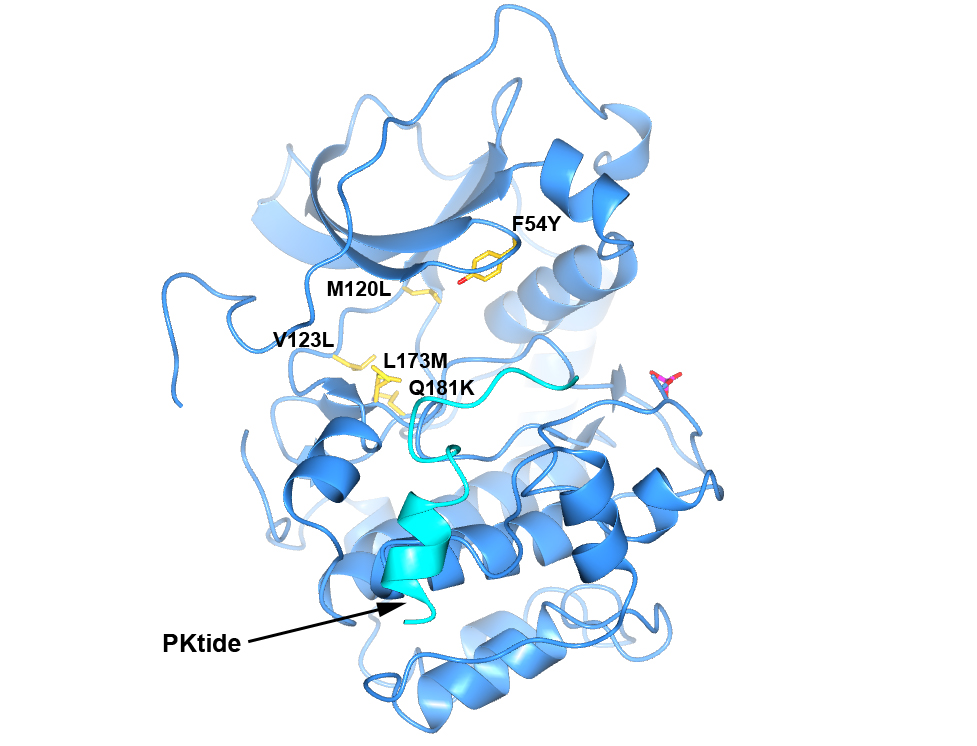

Figure 4. Structure of PKA with the five mutations in and near the ATP-binding site highlighted in yellow. The PKtide substrate inhibitor is shown in light blue

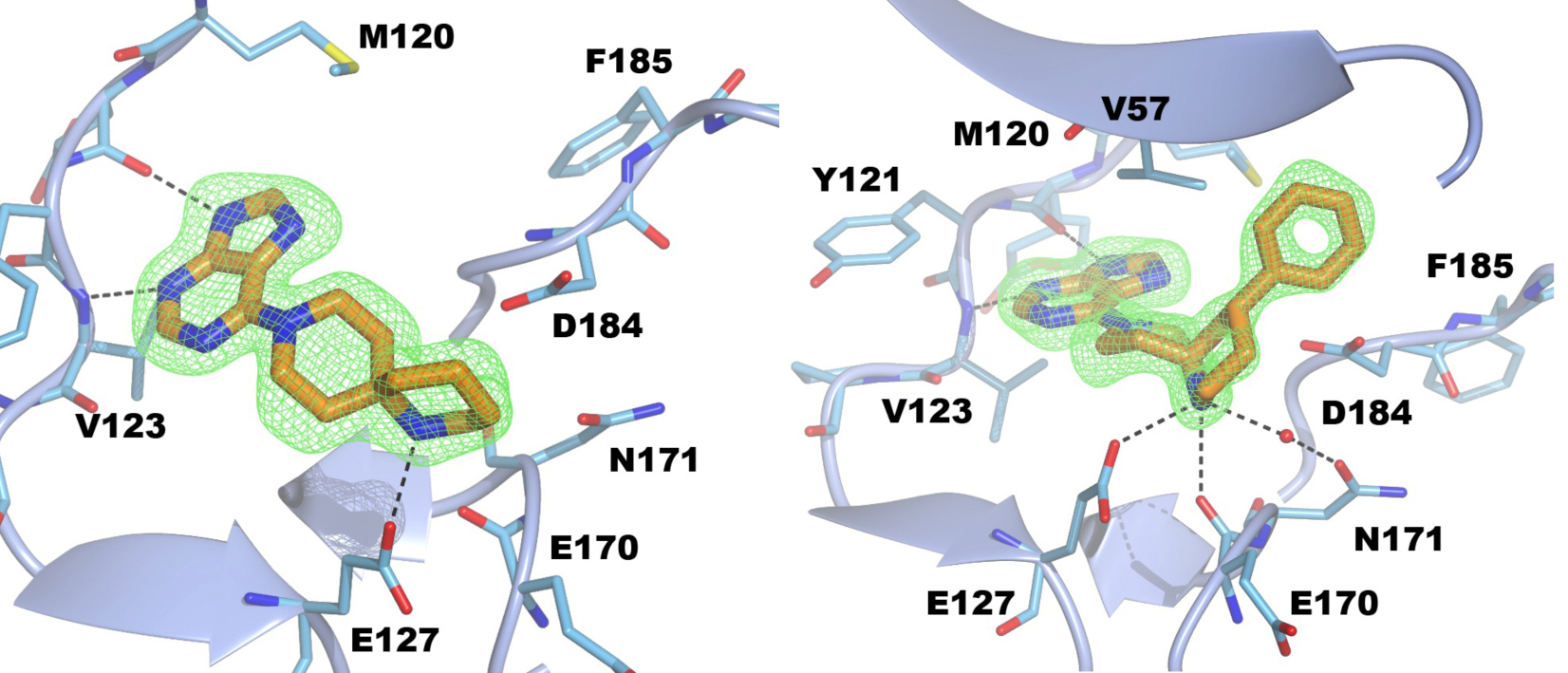

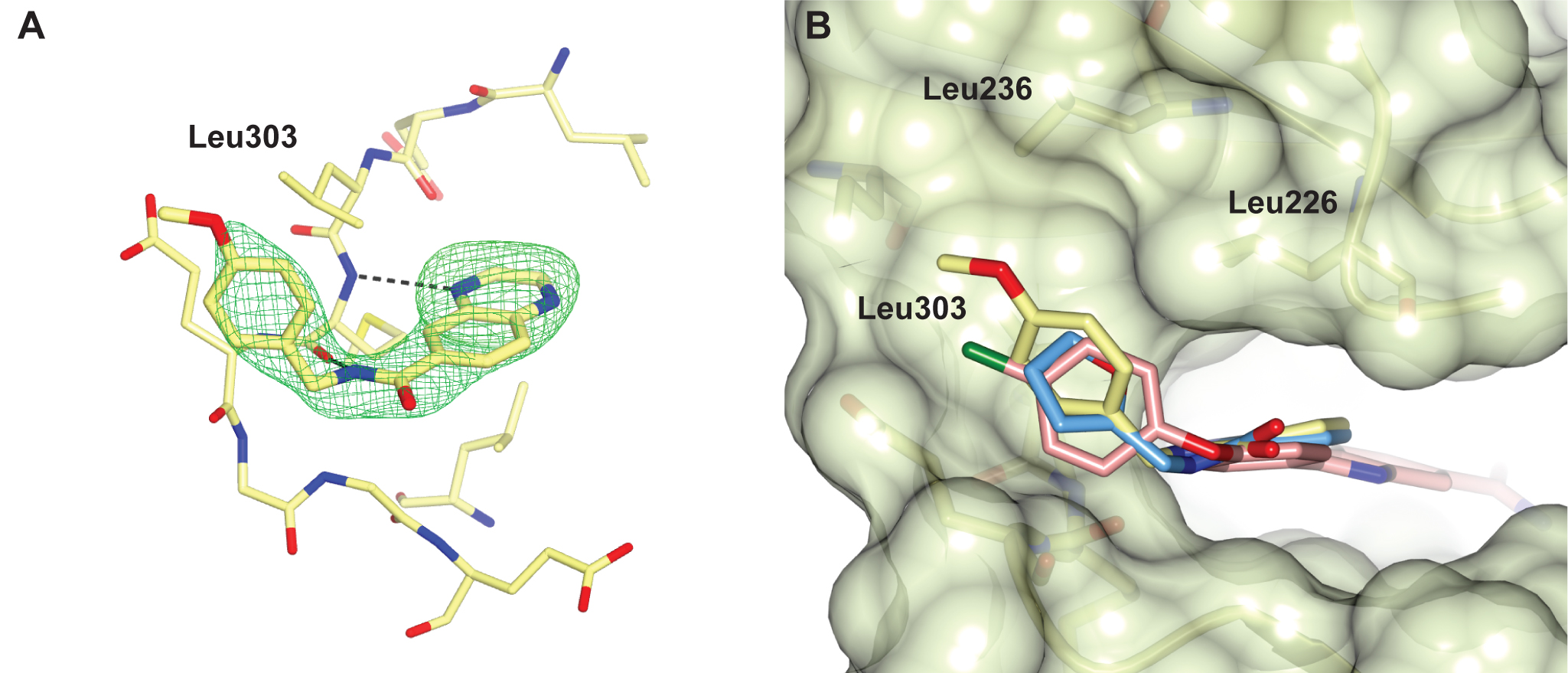

Figure 4. Structure of PKA with the five mutations in and near the ATP-binding site highlighted in yellow. The PKtide substrate inhibitor is shown in light blue Figure 5. S6K inhibitors bound in the PKA-S6K1 chimeara. A) High resolution structure (2.2Å) of a carboxamidobenzimidazole HTS hit bound in the PKA-S6K1 ATP binding site. B) High resolution structure (1.6Å) of a benzimidazole oxadiazole S6K inhibitor bound in the PKA-S6K1 ATP binding site.

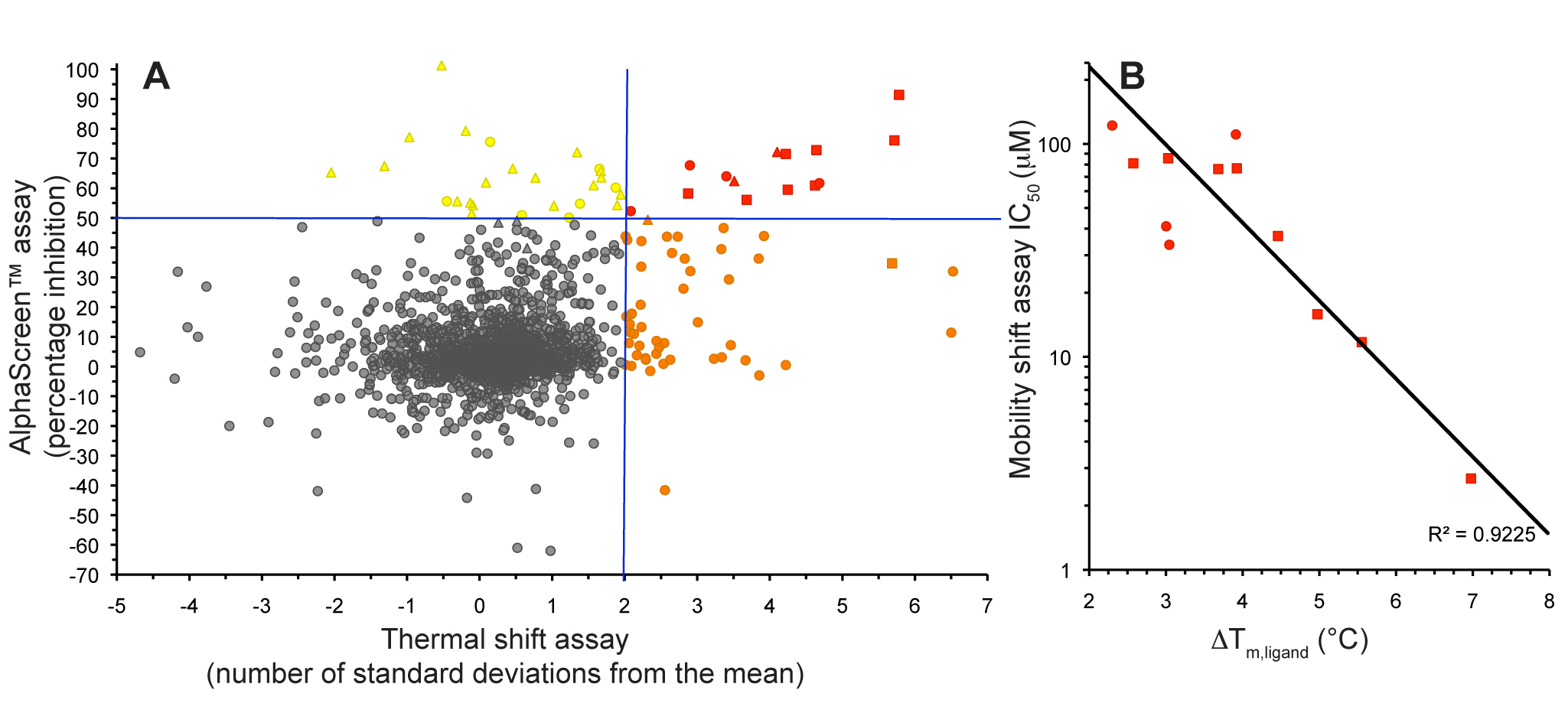

Figure 5. S6K inhibitors bound in the PKA-S6K1 chimeara. A) High resolution structure (2.2Å) of a carboxamidobenzimidazole HTS hit bound in the PKA-S6K1 ATP binding site. B) High resolution structure (1.6Å) of a benzimidazole oxadiazole S6K inhibitor bound in the PKA-S6K1 ATP binding site. Figure 1. Fragment screening data from biochemical and thermal shift assays. (A) Comparison showing the primary AlphaScreen™ data plotted along the vertical axis as percentage inhibition, and the thermal shift data plotted along the horizontal axis as the number of standard deviations from the mean Tm, ligand for each plate and thresholds displayed as blue lines Hits in AlphaScreen™ and thermal shift are displayed in yellow and orange respectively. Mutual hits are shown in red, inactive fragments are grey. (B) Comparison of the IC50 and DTm, ligand values for the screening hits. Fragments showing interference in the AlphaScreen™ are indicated as triangles. Fragments confirmed in crystallography are shown as squares.

Figure 1. Fragment screening data from biochemical and thermal shift assays. (A) Comparison showing the primary AlphaScreen™ data plotted along the vertical axis as percentage inhibition, and the thermal shift data plotted along the horizontal axis as the number of standard deviations from the mean Tm, ligand for each plate and thresholds displayed as blue lines Hits in AlphaScreen™ and thermal shift are displayed in yellow and orange respectively. Mutual hits are shown in red, inactive fragments are grey. (B) Comparison of the IC50 and DTm, ligand values for the screening hits. Fragments showing interference in the AlphaScreen™ are indicated as triangles. Fragments confirmed in crystallography are shown as squares.

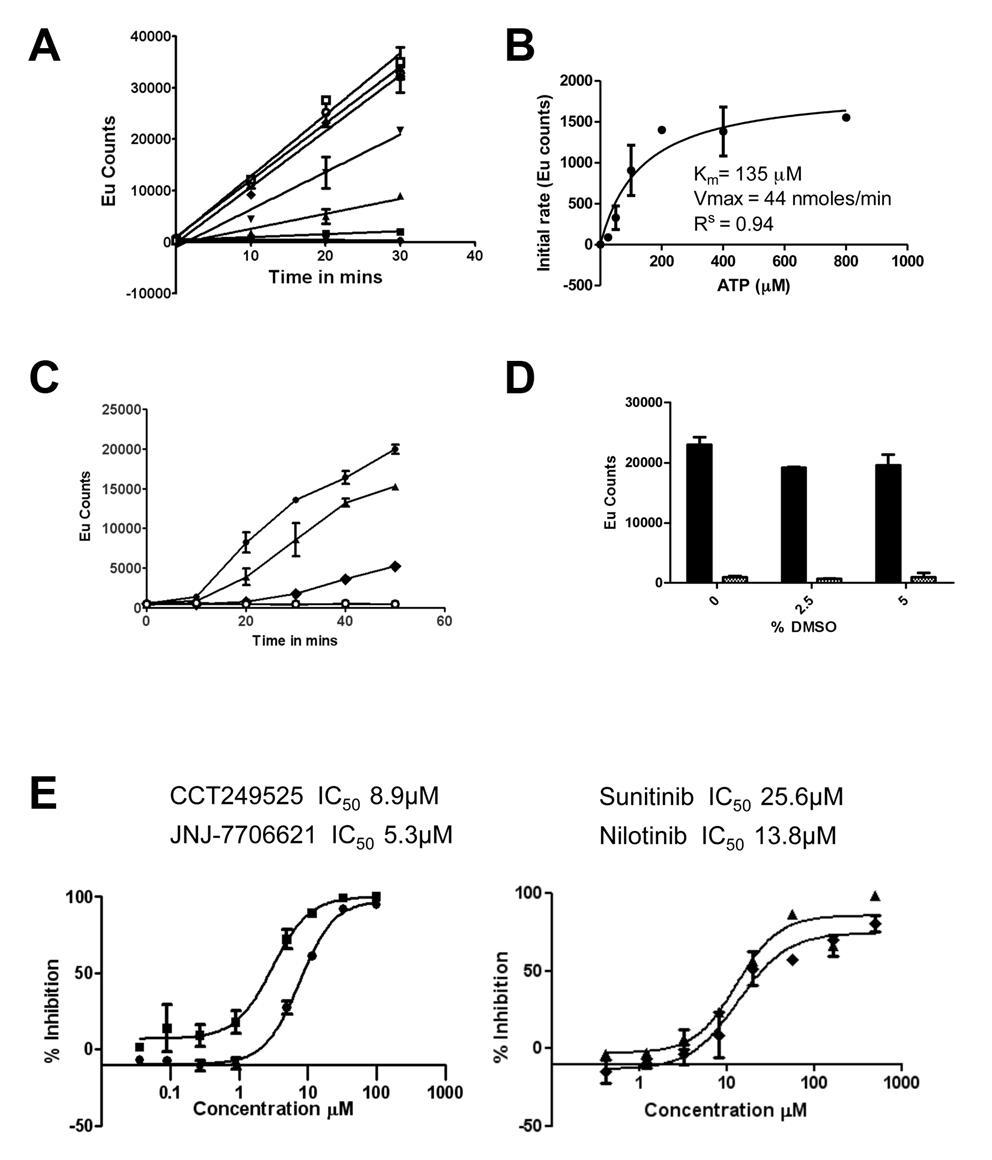

Figure 1. The IRE1α autophosphorylation DELFIA® assay. (A) Time course with varying ATP concentrations used to calculate the Km for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (● no ATP, ■ 25 µM ATP, ▲ 50 µM ATP, ▼100 µM ATP,♦ 200 µM ATP, ○ 400 µM ATP,□ 800 µM ATP). B) Determination of the Km for adenosine triphosphate (ATP). C) Enzyme reaction time course; mean +/- SD of n=2 wells (● enzyme reaction at 700 nM IRE1α and 100 µM ATP, ▲ enzyme reaction at 500 nM IRE1α and 100 µM ATP, ♦ enzyme reaction at 350 nM IRE1α and 100 µM ATP,○). Enzyme reaction at 700 nM IRE1α without ATP). D) Effect of DMSO on the IRE1α autophosphorylation DELFIA®, showing no effect on the assay with up to 5% DMSO. E) Inhibition of IRE1α autophosphorylation activity by CCT249525 (●) , JNJ-7706612 (■), Sunitinib (♦) and Nilotinib (▲).

Figure 1. The IRE1α autophosphorylation DELFIA® assay. (A) Time course with varying ATP concentrations used to calculate the Km for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (● no ATP, ■ 25 µM ATP, ▲ 50 µM ATP, ▼100 µM ATP,♦ 200 µM ATP, ○ 400 µM ATP,□ 800 µM ATP). B) Determination of the Km for adenosine triphosphate (ATP). C) Enzyme reaction time course; mean +/- SD of n=2 wells (● enzyme reaction at 700 nM IRE1α and 100 µM ATP, ▲ enzyme reaction at 500 nM IRE1α and 100 µM ATP, ♦ enzyme reaction at 350 nM IRE1α and 100 µM ATP,○). Enzyme reaction at 700 nM IRE1α without ATP). D) Effect of DMSO on the IRE1α autophosphorylation DELFIA®, showing no effect on the assay with up to 5% DMSO. E) Inhibition of IRE1α autophosphorylation activity by CCT249525 (●) , JNJ-7706612 (■), Sunitinib (♦) and Nilotinib (▲).

.

.

.

.