Ollie Richards, Advocacy Manager at the ICR, explores how a critical element of the Government's research funding – the Charity Research Support Fund – could be reformed to help support more specialist institutions and universities to do life-saving research.

Charity-funded research saves and changes lives.

I’ve seen first-hand how it drives progress across cancer research and treatment – and, most importantly, improves patient outcomes. I’ve spoken to our inspirational researchers, working on charity-funded projects driving changes for those affected by cancer. I’ve met countless patient advocates who credit extra time with loved ones, their ability to make new memories, and even their own personal survival, to breakthroughs made possible by charity-funded research that’s happened at UK specialist institutions and universities.

The UK’s research ecosystem is unique. In no other country, do medical research charities play such a central role in funding life-sciences research or do universities so consistently lead this research from basic discovery all the way to its translation into real-world impact. This partnership is one of our greatest national assets. According to the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC), 87 per cent of the £1.6bn invested by its members in 2024 went through universities. At the ICR, we’re proud of the special partnerships this model enables – from our Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre in Chelsea, to our Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence in Sutton, and our long-standing collaborations with Cancer Research UK across both our campuses to name but a few!

Cost recovery in our universities

To manage this, universities track the ‘cost recovery’ of the income they receive from charity research grants compared against the ‘full economic cost’ of conducting specific research projects. Data from the Office for Students’ ‘Transparent Approach to Costing’ exercise show that on charity-funded research, we at the ICR recover only 57 per cent of the true cost of conducting that research. Therefore, for every £1 we receive from a charity, we must find another 43p from other sources to cover the full cost of the work. As an organisation, we are highly successful in winning competitive, peer-reviewed research grants from medical research charities, with more than 60 per cent of our research income coming from charitable sources – translating this across our charity research portfolio equates to an annual shortfall of £26 million on charity research income alone.

Charity Research Support Fund – the planned solution

Recognising this problem, in 2006, the Government created the Charity Research Support Fund (CRSF). Its aim was to ensure the financial sustainability of charity-funded university research – and to acknowledge the immense value of this partnership to the UK’s research base. In effect, CRSF allows the Government to protect charity investment in universities at relatively low cost, ensuring universities receive ‘top-up’ funding so that they aren’t left to shoulder the financial burden alone whilst enabling charities to pick up the burden of investment that successive governments have failed to.

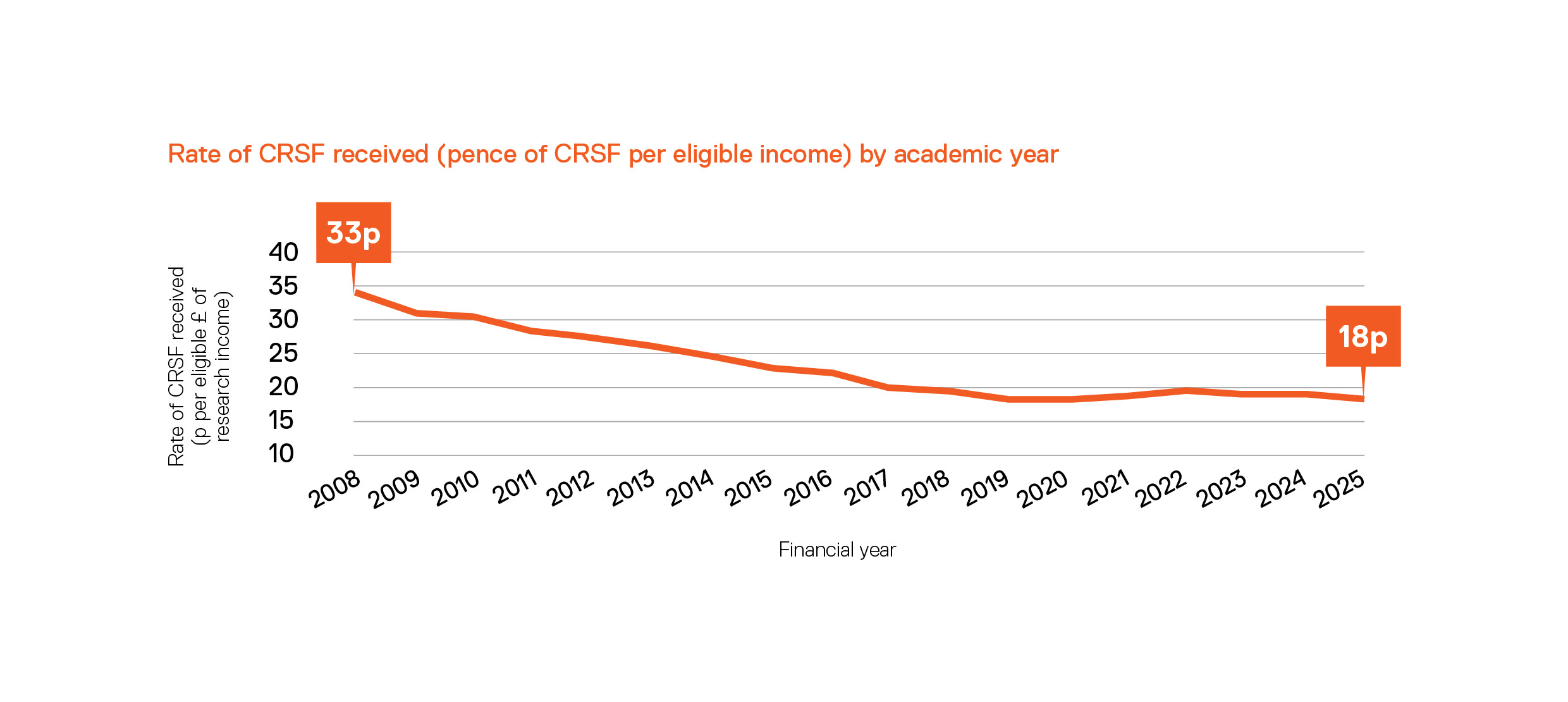

In 2008, universities received 33p of CRSF support for every £1 of charity funding reported – offering a degree of cost recovery that helped to support their financial sustainability.

But the CRSF has failed to keep pace with reality. The fund currently stands at £219 million – far short of the £270 million originally expected by 2010 – while charity investment has continued to soar; more than doubling between the introduction of CRSF and 2023. The result? The relative value of CRSF has fallen sharply as there’s significantly more competition for an under-funded and under-pressure pot of money. The pence per pound figure is now down to 18p of CRSF support per £1 of charity income reported - forcing institutions to absorb growing deficits that threaten the long-term sustainability of charity research in universities.

CRSF allocations are calculated on a pro-rata basis against research income over the most recent four-year period. In theory, this approach reflects relative performance: a university that secures 10 per cent of England’s charity research income receives 10 per cent of the CRSF. However, in reality, this means a small number of large universities now receive a disproportionate share of the CRSF pot: three institutions take 44 per cent of the total fund, leaving the remaining 112 institutions to share what’s left. The most recent allocation of CRSF awarded us at the ICR £8.7 million – valuable, but nowhere near enough to cover our £26 million shortfall. As a specialist postgraduate institution, we don’t have other large income streams such as international student income to help plug this gap. This means that we’re less able to invest in the latest cutting-edge equipment, or innovative research leaders which help maintain our global competitiveness as an institution because we are covering deficits from research grant income – not a position any organisation wants to find themselves in.

To return the fund to the relative value to universities of 33p in the pound would require £176 million of additional investment by Government annually (on top of the current £219 million). While this is where the fund should be after years of underinvestment, we recognise the current financial pressures and that an ask of £176 million may be challenging. Therefore, we have modelled an alternative approach that significantly reduces the cost to Government.

The introduction of a cap – an alternative solution

The issue of cost recovery has recently gained traction following the ‘Post-16 Education and Skills’ White Paper, which acknowledged the growing financial strain on the research sector. We now have an opportunity – and we have a ready-made solution – to address it. Our proposal, modelled at two levels, would improve cost recovery for charity-funded research at a fraction of the cost of previous calls for intervention in this area. More than 97–99 per cent of institutions receiving CRSF would benefit. The time for incremental fixes has passed – we need creative, practical reform before it’s too late.

The CRSF’s biggest challenge is that it’s a relatively static pot of funding. In the same period where charity investment has more than doubled, CRSF has been subject to only two modest uplifts: an additional £6 million in 2018/19 and a further £15 million in 2022/23 bringing the annual pot to £219 million. In today’s fiscal climate, significant increases to this pot from the Government are unlikely – despite repeated calls from the sector. Therefore, to make the fund fairer and more effective, we propose introducing a cap on the maximum average eligible income used to calculate CRSF allocations. This means that there is a limit to the amount of CRSF support a university can receive and if they meet the maximum amount of income they are allowed to report (the cap) then they will not receive any further CRSF support. They will still receive a lot of money – either £23 million or £33 million depending on where the cap is set – based on current modelling but importantly there is a limit to how much of the total CRSF pot they can receive – this means that there is more to go round for every other institution.

This would rebalance the distribution of CRSF, ensuring that smaller and mid-sized universities receive meaningful support rather than being crowded out by the biggest recipients. Similar caps already exist in other Research England funding streams – including the Research Culture, Participatory Research, Policy Support Fund, and HEIF programmes – to ensure fairer distribution of limited public funds.

Our proposal is modest and proportionate. The introduction of a cap on the maximum average eligible income means a much smaller investment from Government would be required to return CRSF to the relative value of 33p in the pound – a level last seen in 2008, which would provide more certainty and support to the majority of institutions. With the introduction of a cap, 112 institutions would receive an 80% increase in their CRSF allocation.

Without reform and the introduction of a cap, the Government would need to add an additional £176 million annually to the CRSF pot to simply to restore CRSF’s value to 2008 level delivering the 33p in the pound figure. A cap delivers the same outcome more efficiently by uplifting the CRSF income of the vast majority of recipients from a smaller investment from Government– saving money while protecting and improving the financial sustainability of almost every university across England. The small reductions affecting either one or three large institutions (depending on the cap level) are modest compared to their overall budgets.

We have modelled the impact of a cap at two different levels, using Research England data, based on the current CRSF budget of £219 million:

A £100 million cap on the maximum eligible income used to calculate CRSF allocations would require a Government uplift to the CRSF fund of £100.5 million annually.

This would see 114 institutions receiving more CRSF and only one institution receiving a slightly smaller allocation. 112 of these institutions would receive an 80 per cent increase, whilst 2 more would receive smaller increases.

A £70 million capon the maximum eligible income used to calculate CRSF allocations would require a Government uplift to the CRSF fund of £68.4 million annually.

This would see the same 112 institutions receive an 80 per cent increase in their CRSF allocation. Only the top three recipients would see modest reductions in their CRSF allocation.

In today’s tight fiscal environment, we must think differently about how to safeguard the UK’s research strength and improve universities’ financial sustainability. A cap on CRSF allocations offers a simple, transparent, and cost-effective solution to the problem of poor cost recovery for charity-funded research. We shared this proposal with the Government ahead of the Budget and would welcome the opportunity to work together on its implementation.

By acting now, Government can protect the UK’s unique charity–university research partnership, support financial sustainability across the sector, and ensure that every pound donated to medical research continues to deliver sustainable, life-changing impact for decades to come.