Timeline: How we have led the way in childhood cancer research

We are internationally leading in the study of cancers in children, teenagers and young adults. From uncovering the genetic drivers of disease to developing kinder, more targeted treatments, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, has been at the forefront of childhood cancer research for decades.

1950s

- ICR scientists began work on a family of chemotherapy agents, inspired by research at Yale University into nitrogen mustard. They chemically modified the compound to improve tumour uptake, leading to the discovery of melphalan and chlorambucil, followed by busulphan. All three drugs became foundational treatments for childhood cancers and are still in use today.

1960s - 1980s

- In 1965, the ICR played an important role in the development of cisplatin, which was originally discovered by a research team at the University of Michigan. ICR researchers demonstrated that the drug acted in a similar manner to alkylating agents, compounds that damage DNA and kill cancer cells. Cisplatin became the backbone of combination therapy, often prescribed alongside an alkylating agent, and it was widely used in treating solid tumours in children.

- During the 1970s, the ICR helped develop carboplatin, a less toxic alternative to cisplatin that is now a common treatment for childhood cancers.

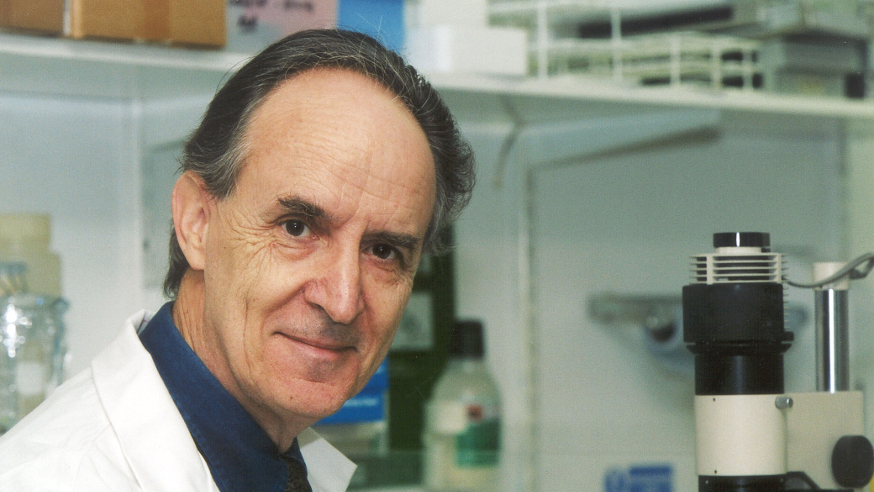

- In the 1980s, Professor Sir Mel Greaves was recruited to establish the UK’s first Leukaemia Research Fund Centre. Professor Greaves improved our understanding of childhood leukaemia, which allowed treatments to be better tailored to each child or young person.

1990s

- In the 1990s, ICR researchers led pioneering work in identifying cancer predisposition genes, including those linked to childhood cancers. By studying inherited mutations and conducting large-scale studies, they discovered specific genes that can cause childhood cancers when both copies are mutated. These insights have helped clinicians predict cancer risk and guide surveillance and prevention strategies.

- In 1992, the United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study (UKCCS) – one of the most comprehensive investigations into the causes of childhood cancers, including leukaemia – was initiated. ICR researchers played a pivotal part in the study as one of the key research centres responsible for data collection and analysis.

2000s

- In 2005, Drug Development Unit was established as a joint initiative between the ICR and The Royal Marsden. It became one of the largest early-phase clinical trial programmes in the UK, running trials for both adults and children.

- From the early 2000s, Professor Sir Mel Greaves and his team undertook decades-long research that provided evidence for earlier theories about the origins of childhood leukaemia. Their work confirmed that the disease begins before birth and uncovered new insights into how it progresses – including the role of cancer stem cells, early genetic changes, and how folic acid exposure during pregnancy may reduce leukaemia risk. The researchers also identified various environmental factors that may trigger or influence disease development, including postnatal infections, lack of early immune priming and the gut microbiome.

2010s

- In 2012, an international collaboration co-led by researchers at the ICR examinedthe medical records of 8,800 neuroblastoma patients from around the world to identify several large-scale genetic faults that were strongly linked to survival rates. The researchers concluded that a whole-genome scan would be more effective at predicting prognosis than tests for individual genetic factors.

- In 2014, as part of a global effort, researchers at the ICR made a breakthrough in understanding the cause of rhabdomyosarcoma – a rare soft tissue cancer that mainly affects children and young people but can also occur in adults – by revealing the key role of a protein called Yap in triggering the disease.

- In 2014, ICR researchers led by Professor Chris Jones discovered a remarkable link between a type of childhood brain cancer, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), and an inherited disorder known as stone man syndrome. The finding was unexpected, surprising and intriguing to the researchers who made the discovery and could ultimately help lead to new treatments for children with DIPG.

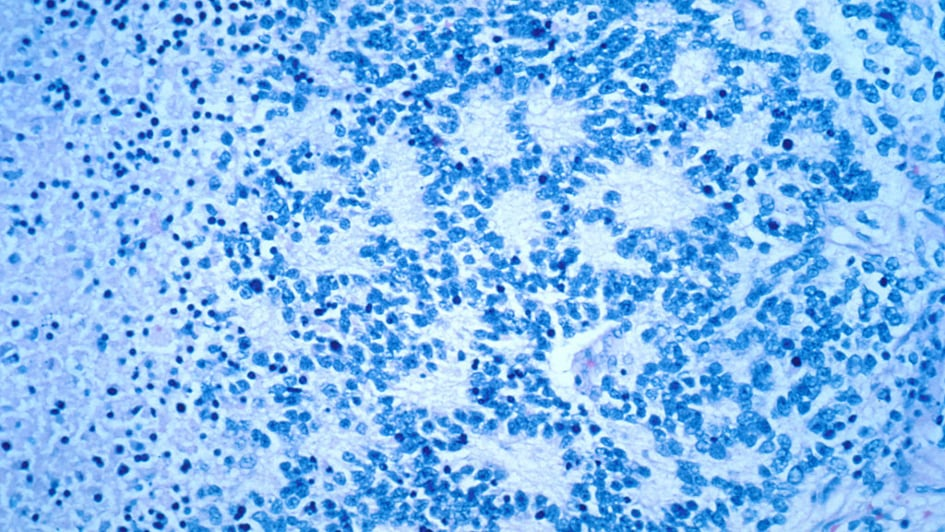

- In 2016, researchers at the ICR discovered that a potent inhibitor can effectively shrink childhood cancers, such as neuroblastoma, by blocking key metabolic pathways. As a result, several drugs that target these inhibitors entered paediatric clinical trials, offering new hope for treating aggressive childhood cancers.

- In 2017, scientists at the ICR identified a new genetic cause of Wilms tumour, a childhood kidney cancer. Our researchers used a technique called exome sequencing to analyse all the genes in 20 families with a genetic disorder called mosaic variegated aneuploidy (MVA) syndrome, which has been linked to Wilms tumour. The findings help families understand why their child developed cancer and offer insights into cancer risk and how genetic errors contribute to disease.

- In 2018, Professor Greaves assessed the most comprehensive body of evidence ever collected on acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) – the most common type of childhood cancer. His research concludes that the disease is caused through a two-step process of genetic mutation and exposure to infection that means it may be preventable with treatments to stimulate or ‘prime’ the immune system in infancy.

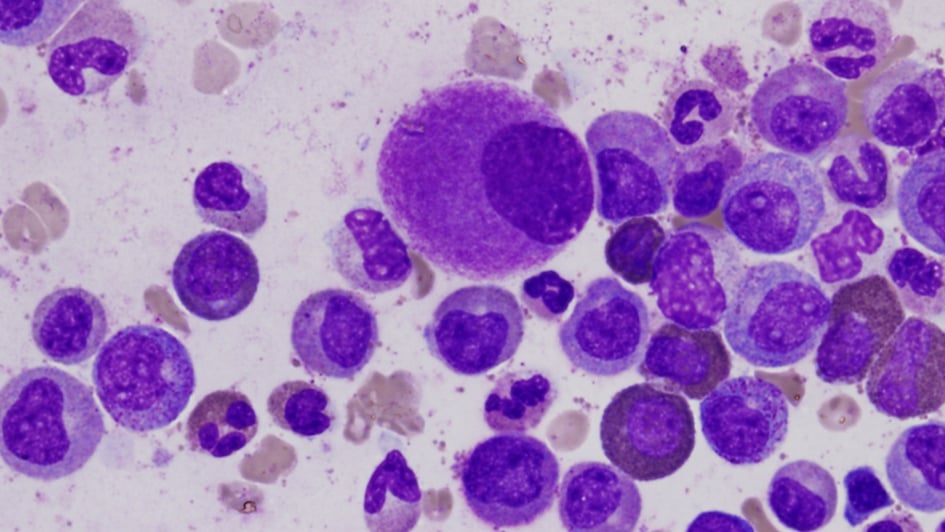

- In 2019, ICR scientists created a new mouse model that accurately mimics how neuroblastoma spreads in children. The model allows researchers to see the development of resistance to chemotherapy and the spontaneous spread of cancer to the bone marrow, making it a powerful tool for testing new treatments.

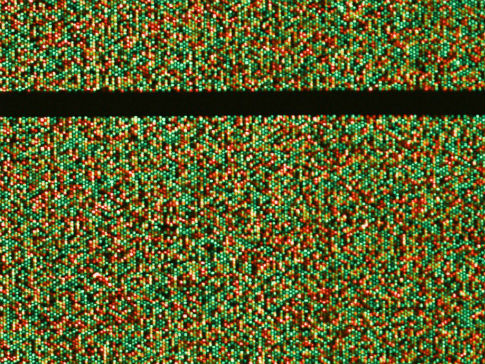

- In 2019, a study led by Professor Louis Chesler built on the 2016 launch of a pioneering gene panel test developed at the ICR and The Royal Marsden. That earlier test, which sequenced key cancer genes from small tumour samples, aimed to match children to targeted therapies and reduce reliance on chemotherapy. Professor Chesler’s team used an expanded version of the test to analyse 91 genes in tumour samples from over 200 children. The study showed that more than half had mutations that could potentially be treated with adult cancer drugs – and those who received targeted therapies saw significant benefits. The findings marked a major advance in precision medicine for young patients.

2020s

- In 2020, Professor Chesler and his team published findings showing that a drug co-discovered at the ICR, fadraciclib, could significantly shrink aggressive neuroblastoma tumours in preclinical models. Unlike the 2016 discovery, which focused on blocking metabolic pathways using mTOR inhibitors, this drug works by indirectly targeting a different gene that drives high-risk neuroblastoma, offering an alternative route to precision treatment.

- In 2020, results from the largest and most comprehensive study of infant glioma, led by Professor Chris Jones, identified the disease as biologically distinct from that in older children, helping explain why the tumours in those aged below one tend to be less aggressive. The study also showed that babies could, in some cases, be successfully treated with targeted drugs, sparing them from chemotherapy.

- In 2021, Professor Janet Shipley led the largest and most comprehensive study of rhabdomyosarcoma to date, which revealed key genetic changes underlying the development of the aggressive disease. The findings could lead to improved decision making in assigning treatments for children. The researchers are incorporating the new insights into the design of clinical trials aiming to improve the management of the disease.

- In 2021, building on this foundation of The Oak Foundation Drug Development Unit, the Centre for Paediatric Oncology Experimental Medicine (POEM) was launched to accelerate the development of innovative treatments for children and young people with cancer. Led by Professor Louis Chesler and Dr Lynley Marshall, POEM works closely with the Oak Paediatric and Adolescent Drug Development Unit to deliver biomarker-driven trials and translational research.

- In 2025, as part of the Stratified Medicine Paediatrics 2 (SMPaeds2) programme – a major research initiative investigating relapse in childhood cancers, which builds on earlier work to develop a genetic test to guide treatment, investigates blood cancers and solid tumours in children and young people, including in the brain, muscle and bone – which can be more difficult to access, diagnose and treat – researchers at the ICR developed a liquid biopsy test that will help them better understand children’s cancers and pave the way for new targeted and less toxic treatments.

Your support helps

Our vital research is made possible thanks to the generosity of individuals and organisations who support our work. Please donate today to help us to continue to make the discoveries that will one day defeat children’s cancer and make a difference to the lives of patients and their families everywhere.