Peter Laing was diagnosed in November 2024, with stage 2/3b high-risk prostate cancer. Now retired, his former career in the biotech industry has helped to inform decisions about his treatment, which has included abiraterone, a drug that was discovered and developed by our scientists. Over a year on from his diagnosis, he reflects on what he describes as a ‘rollercoaster journey’.

My symptoms began more than ten years ago. I was having urinary flow issues and went to my local GP where I was examined and told I had a bit of prostate hyperplasia (basically an enlarged prostate) – nothing to write home about. I was given some tamsulosin tablets to help with my symptoms. ‘Just relax and take the tablets,’ was the message. But the symptoms continued, and I didn't get on with the tablets. I went to see another doctor at the same surgery, and they told me not to worry about it too much.

I didn't know at the time that you have to ask for a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, the blood test that can show raised levels of a protein that may indicate cancer.

Then a friend of mine told me he’d been given PSA test as part of a general health MOT, and I did wonder why I hadn’t been offered one.

By this time, we’d moved house. I was still worried about my prostate, so I took myself down to the new GP. She examined me then did a PSA test.

My result was 14 and the top of the range is supposed to be four. And then I was invited for an appointment at the North Devon District Hospital. The surgeon examined me and said he could feel something in my prostate. He ordered some imaging, and I was quickly sent for a CAT scan followed by an MRI scan.

When the results came back, the surgeon told me it looked like I had prostate cancer and that he wanted to do a biopsy. I said, ‘Yes, bring it on!’

“It was a fright and a shock”

The biopsy results came back measuring as nine on the Gleason scale which is used to grade prostate cancer. I was told if you're nine or 10, it's the top of the charts and you really need some kind of treatment as soon as possible.

At the time it was a bit of a fright and a shock. But I know enough about medicine to realise that these things can be fairly random. So I didn’t think ‘Why me?’ or consider it unfair.

Instead, my first thought was ‘whoa, what stage is it at and has the cat got out of the bag - has it spread?’

The next step was a bone scan, and then I was given a list of treatment options: surgery, radiotherapy, brachytherapy, followed by more radiotherapy. They didn't recommend a particular course of action - it was up to me to choose.

I said I’d like to have internal removable rod brachytherapy, followed by external beam radiotherapy. And then out of the blue, I was told the bone scan showed the cancer appeared to have spread to my spine. All of a sudden, my options had changed and I was being offered palliative treatment instead.

I did some research and asked for a PSMA scan. This looks for the Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen, which is totally different from PSA. It's only present on the surface of prostate cancer cells and normal prostate cells. The radioactive scan shows where the cancer cells are in the body, with any radioactivity found outside the prostate indicating spread of the cancer.

I was offered a PSMA scan in five weeks, but I knew by waiting, I would be on a knife edge between palliative therapy and ‘curative intent’ treatment. I decided to get it done privately and we went through an anxious few weeks.

The PSMA scan confirmed very certainly that the cancer had not spread to my spine. And in fact, when I thought about it, just before Christmas, I’d fallen off a chair when fixing the lights in the kitchen, and I hurt my coccyx at the base of the spine, so that was probably what had shown up on the bone scan.

I was pleased that the bone scan radiographer had been properly vigilant to flag it, but all the doctors agreed, given the PMSA scan result, that I could go back to the original treatment plan that I was offered, with curative intent. So I entered the next stage of my journey.

We urgently need better ways to detect prostate cancer earlier, predict drug resistance, and develop smarter, more personalised treatments. By supporting us today, you can help our scientists make more discoveries and help ensure that every man with prostate cancer can live longer, healthier lives.

Support us

“My experience in drug development informed my treatment choices”

My first instinct had been to opt to have my prostate removed by surgery. But when I did a little bit of research, I found that the better outcomes for my stage of the disease appeared to be from radiotherapy. I was given a choice of different types of radiotherapy, and I decided to have the combination of removable rod radiotherapy, followed by external beam radiotherapy. I had read that the best results from the various clinical trials are with a combination of the two types of radiotherapy, combined with hormone-based androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). The good thing about the internal rod is it enables very high levels of radioactivity to be delivered to the cancer cells. Because it's inserted into the prostate only temporarily, it means that the risk of damage to bladder or bowel function is relatively low.

Because of my experience in drug development, I worked out from the trials that abiraterone (which was discovered and developed by the ICR) seemed to be the best ‘add on’ drug for my stage of disease, providing more-complete androgen deprivation than hormone therapy, and I felt that in my case, receiving it later (should metastatic disease emerge) would be a case of closing the door after the horse had bolted.

I was then alarmed to learn that the drug was not available in England on the NHS despite being licensed for use in Scotland for two years. As an inventor, I was mortified to think that a drug discovered and developed in England, should be so readily obtainable elsewhere but not here, except under private prescription.

I sought the drug under private prescription and eventually I was able to obtain it. I have been on the drug for nine months.

I was delighted when NHS in England approved abiraterone for patients such as myself with high-risk localised prostate cancer.

I was aware that abiraterone was developed by the medicinal chemistry team of the ICR and proven to reduce fatalities by 50% in an exemplary, heroic even, programme of clinical research involving more than 100 hospitals in the UK and Switzerland by Professor Nick James and colleagues.

In my opinion abiraterone is a wonder drug and I feel very optimistic about ultimately beating prostate cancer with the help of this drug, and the support of the excellent NHS team who are looking after me. It is so important to me that this drug is available to every man who needs it under the NHS, and I am forever grateful for the good work of Prostate Cancer UK and others who have kept the faith.

"I consider myself very lucky"

My treatment so far has had relatively few side effects, apart from the obvious ones for being on androgen deprivation therapy such as occasional tiredness, loss of sex drive and erectile dysfunction. I am scheduled to be on androgen-deprivation for a further fifteen months.

I consider myself very lucky, really. But I think if I hadn't been so knowledgeable in terms of how diagnostics work, and how sometimes, even with the most skilled of operators, they can be wrong, it might have been a different scenario.

I could well have been on palliative therapy, instead of the curative intent pathway I’m currently on, which aims to eliminate the cancer completely, rather than enabling me to live with it.

I’m now six months out of radiotherapy and have been on abiraterone for nine months. My PSA level is below the limit of detection and has been so for months now. So, it's looking good and I'm feeling good.

My aspirations are that when I come out of it all and finish treatment, I'll be relatively back to normal again. I was advised that radiotherapy confers a very modest increased risk of colon cancer, but it is a risk have been very willing to embrace, given the effectiveness of the treatment.

"I’ve found my voice"

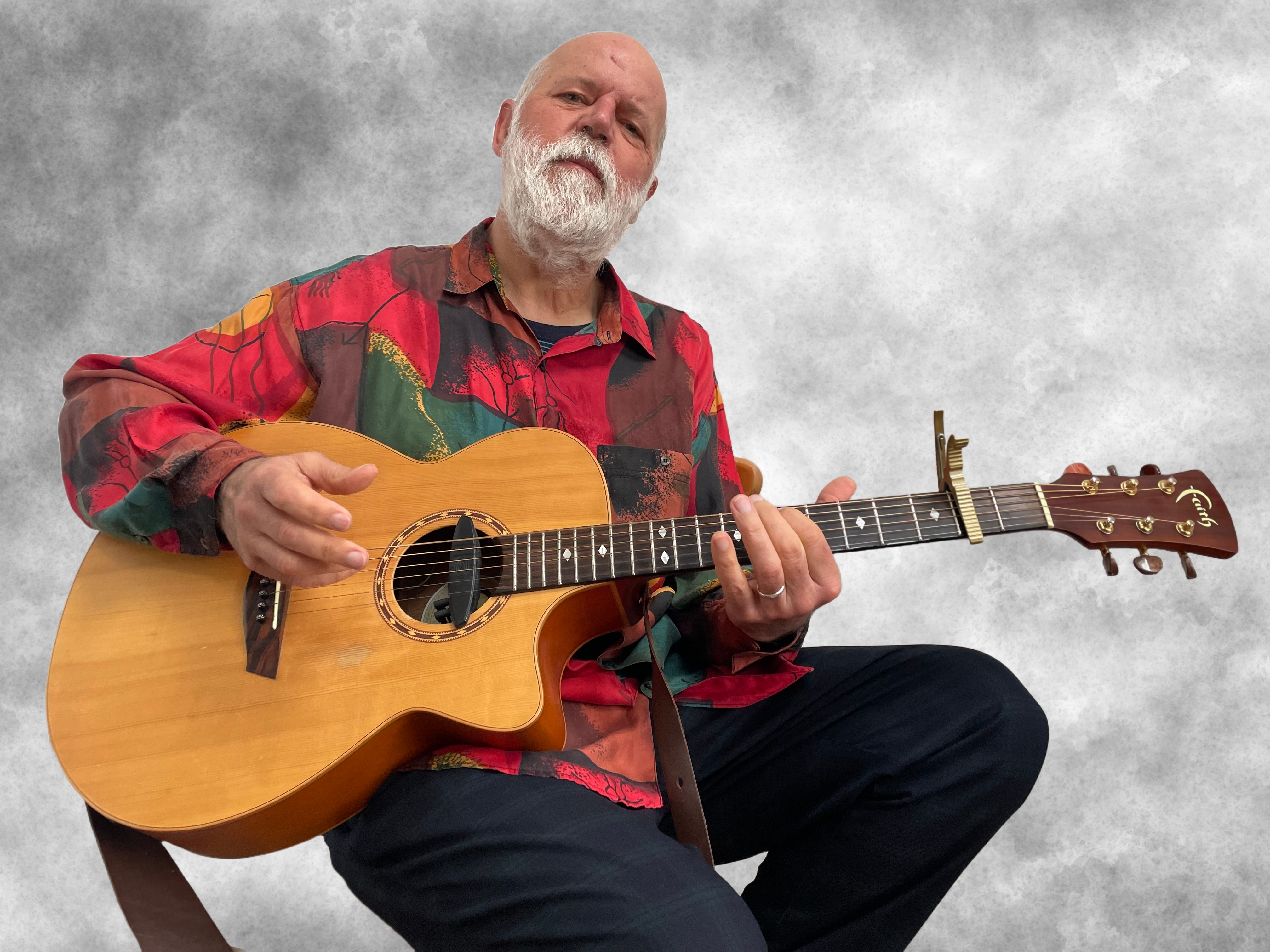

I'm a researcher by trade over many years, but when I retired in 2023, I switched and became a singer songwriter.

I've played in in bands and written songs for years, but I've never really had the confidence to sing them until recently, when I took singing lessons for the first time. I used to croak backing vocals in in the various bands I was in, but now I’ve really found my voice and have been writing songs all the more as a result of it. It's great fun.

It's also a joy thing. When you're on androgen deprivation therapy, its effect on the reward system in the brain is significant, and I was conscious of that. And by throwing myself into the music, I've managed to keep that joy factor up. It's an ongoing thing, but it is working, and it's like exercise or going for a walk, one of those things that really helps. I would recommend that anybody who has been diagnosed with cancer, even if they can't sing, should join a choir. I only have to walk only 100 yards to play in different ensembles so I'm collaborating with a number of friends and musicians locally, the town where I live has a very thriving musical community.

As for research I vigorously and wholeheartedly embrace the importance of research in the field of cancer. It's just incredible how things are progressing. It's not straightforward, but I can imagine that in a few years’ time we will have immunotherapies for prostate cancer.

There are ways of using anti-bodies to block the pathways that cancer cells use to evade the immune system. It won't be plain sailing. Some things are working. Some things won't, but there are exciting prospects for combination of immunotherapies and vaccines and other new treatments in the pipeline. In addition to all that there are creative efforts in drug-repurposing, and new drugs in development based on genetic knowledge. I would say that there has never been a more exciting time for cancer research than today, and I continue on a daily basis to be amazed at the dedication of the researchers and the rate of progress.

Our pioneering research is transforming the lives of men with prostate cancer. But too many lives are still lost. Donate today to help fund more groundbreaking discoveries – and give hope to every dad, brother, uncle, partner or friend with prostate cancer.

Donate now