Researchers have uncovered how a key DNA repair enzyme is recruited and activated inside cells, answering long-standing questions about how cells protect and repair their DNA and providing the structural groundwork that could support the refinement of existing cancer therapies.

Led by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, the research team studied an enzyme called XPF-ERCC1, which plays an essential role in repairing damaged DNA and in maintaining genome integrity – the preservation of a cell's DNA structure and sequence – a process that cancer can exploit to promote its survival and growth.

Earlier research had already shown that XPF-ERCC1 acts across multiple DNA repair pathways, but until now, scientists did not fully understand how the enzyme arrives to where it is needed within the cells of our bodies and how its activity is switched on once there.

The study, published in Nature Communications, combined a recently introduced innovative AI system with electron microscopy to answer these pressing questions on DNA repair in molecular detail. The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) – which is both a research institute and a charity – primarily funded this work, with additional support provided by the Medical Research Council.

A long-standing puzzle in DNA repair

Cells are constantly exposed to sources of DNA damage, from normal metabolic processes to environmental stress. To survive, they depend on tightly regulated repair pathways that detect and fix lesions – such as breaks or chemical damage to DNA – before they cause mutations or cell death.

XPF-ERCC1 is a structure-specific repair enzyme that helps fix damaged DNA by cutting it at precise sites as part of the repair process. Rather than recognising a particular DNA sequence, it detects structures that arise when DNA is damaged, allowing it to act wherever repair is needed. However, such DNA structures can also arise under normal circumstances, such as when the genome is being copied when cells prepare to divide.

This makes XPF-ERCC1 a powerful yet potentially dangerous enzyme, requiring strict control of its activity to prevent unwarranted and harmful DNA breaks. One way to control XPF-ERCC1 is to activate it only in specific locations after other proteins have already verified that DNA damage is indeed present. One such XPF-ERCC1-controlling protein is SLX4, which brings XPF-ERCC1 to its sites of action and then stimulates its DNA-cutting function. However, how exactly SLX4 achieves this feat has been unknown so far.

A combined visualisation approach

To visualise this complex, the research team combined AlphaFold – a revolutionary AI system able to predict a protein’s three-dimensional (3D) structure from its amino acid sequence – with high-resolution cryogenic electron microscopy, which uses electrons to generate detailed 3D images of DNA, proteins and other biological molecules.

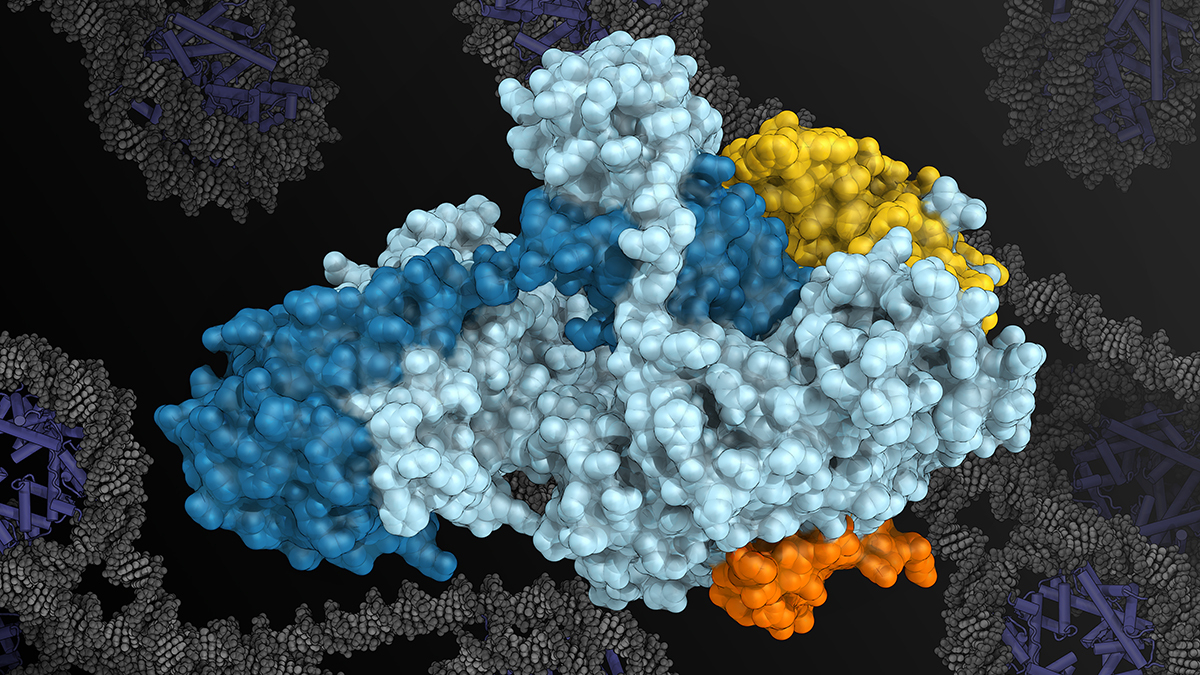

Image: Rendering of the XPF-ERCC1 enzyme complex provided by Dr Basil Greber (XPF in cyan, ERCC1 in blue, SLX4 in orange, SLX4IP in yellow, with DNA wrapped around nucleosomes in the background)

This combination allowed them to pinpoint precise docking-site regions of SLX4 on the surface of XPF-ERCC1, and to show how additional molecular interactions help regulate it once DNA is present. By identifying these sites, the team was able to visualise XPF-ERCC1 in its active state and understand how changes in its structure switch the enzyme on and off. This control allows it to engage with damaged DNA when repair is needed, while remaining inactive at other times.

Why this matters

DNA repair pathways are essential for normal cells, but they can be exploited by cancer cells for survival and growth. Future work will focus on finding ways to interfere with the interactions uncovered in the study, using AI-based approaches to enhance or disrupt specific enzyme relationships within DNA repair complexes.

Senior author Dr Basil Greber, Group Leader of the Structural Biology of DNA Repair Complexes Group at the ICR, said: “Although this research is fundamental in nature and does not have immediate medical applications, it is a meaningful advance. Understanding the mechanisms of these repair enzymes is a vital step towards being able to manipulate DNA repair pathways selectively.

“In the long term, this work lays the groundwork for future efforts to interfere with and manipulate these enzyme complexes. This could help us design precise methods to weaken cancer cells’ ability to repair DNA or maintain the integrity of their genomes, potentially improving the effectiveness of existing treatments for patients.”