Non-small cell lung cancer (photo Dr Ed Uthman/Yale Rosen/Flickr)

We now have an armoury of novel cancer drugs that interfere with specific molecules involved in cancer cell growth and survival. These targeted therapies have given us a significant step forward in cancer treatment.

But although there have been noteworthy successes, patient benefit with single-agent targeted therapies can be significant and sometimes dramatic, but commonly not prolonged. And despite promising results initially, drug resistance is inevitable.

Researchers are now looking outside the historical, well-trodden cancer pathways that are usually targeted by cancer therapeutics. One interesting avenue which is being explored is targeting cancer’s stress response.

Hallmarks of stress

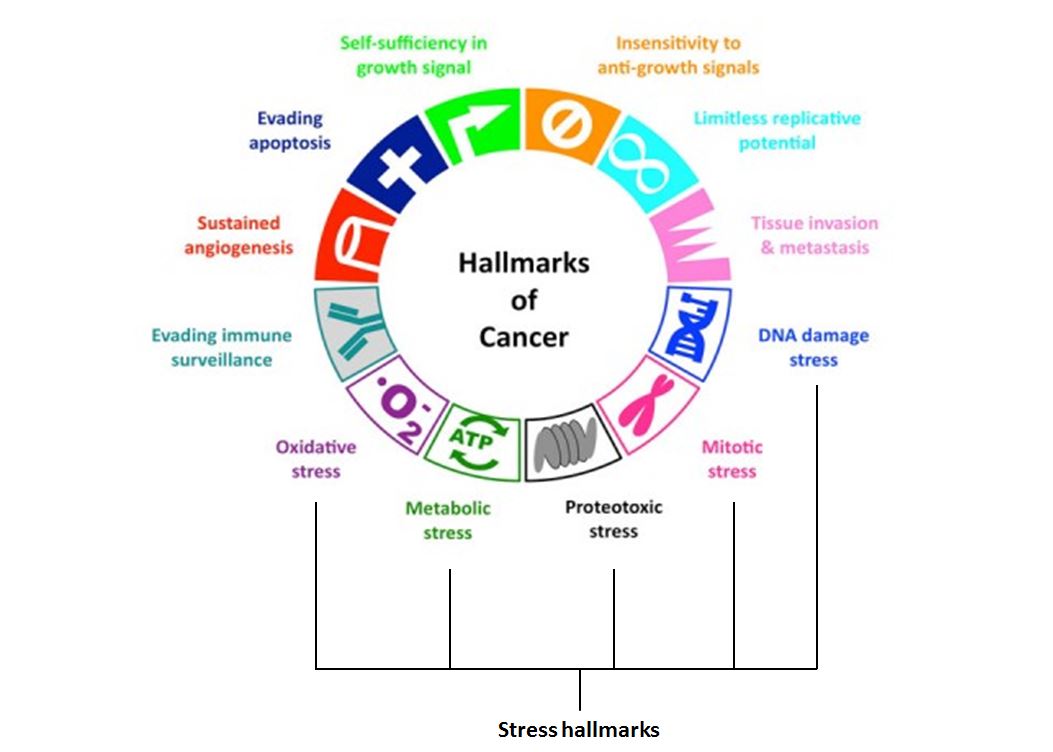

Cancer cells need to withstand huge amounts of stress as they divide rapidly and their metabolism goes into overdrive. Rising to the challenge, they take on particular characteristics, or ‘hallmarks of cancer’, which include invading tissue, limitless replicative potential and metastasis — where cancer spreads around the body.

Recently, a subset of extended hallmarks has been proposed that revolve around stress responses that allow cancer cells to tolerate environments that would usually result in cell death.

Stress responses include DNA damage, altered metabolism and proteotoxic stress — toxicity caused by misfolded proteins. How stress characteristics arise is not well understood, but targeting these hallmarks and their associated vulnerabilities in a wide variety of cancers is now showing promise for therapeutic intervention.

The extended hallmarks of cancer (image adapted from Luo, J., Solimini, N.L. & Elledge, S.J. (2009) Cell Vol.6(136), pp. 823-837)

HSP90 – the master switch

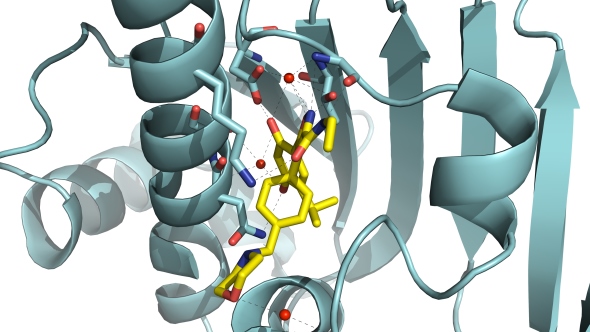

Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is a molecular chaperone, an important protein involved in the folding, function, activation and stability of many other proteins in a cell. But in tumours, cancer cells turn the HSP90 protein to their own ends by using it to subvert the natural process of cell death.

HSP90 also stabilises many proteins involved in driving cancers — including mutated BRAF and amplified HER2, and their drug-resistant forms — allowing them to wreak havoc with normal cell replication to cause uncontrollable cell division and the spread of cancer.

Because HSP90 is critical for many processes that are fundamentally important in cancer, inhibiting it hits cancer hard in several different ways simultaneously, attacking multiple hallmarks of cancer.

HSP90 inhibitors have potential for broad activity across many tumour types and could minimise the opportunity for drug resistance to develop.

Here at the ICR, we have led the way in HSP90 research, developing drugs like luminespib (formally known as AUY922) that are now showing benefits for cancer patients with mutant drivers in early trials.

In the shorter term, HSP90 inhibitors are likely to be used in patients who have become resistant to current treatments, but in the future they could play an even bigger part in tackling cancer as an early-stage treatment and preventing drug resistance arising.

Molecular structure of luminespib (in yellow) binding to HSP90 (image: the ICR)

HSF-1 — the stress protector

Normally the so-called heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) pathway is activated when healthy cells are stressed. Despite the historical name, the HSF1 pathway protects the cell against a range of stressful events by switching on certain genes.

But cancer cells are under constant stress from internal and external influences — including those elicited from cancer driving genes — and rely on the HSF1 pathway to survive.

Researchers at the ICR predict that blocking this pathway using HSF1 pathway inhibitors will stop cancer cells from growing and shrink tumours. It’s hoped that targeting cancer in this completely new way will help to treat many cancers, including cancers where there is a high unmet need for new treatments.

A new way to tackle drug resistance

There have been major steps forward in creating innovative new cancer treatments, but we still see many patients whose cancer has developed resistance to all available drugs so there is an urgent need to find more treatment options.

Cancer cells operate in a highly stressed state, and one tantalising possibility is to target pathways that help cancer cells survive levels of stress that would kill healthy cells. Researchers also believe that attacking these forms of cancer target – like HSP90 and HSF1 – will be a step forward in overcoming the challenge of drug resistance.

-547x410.jpg?sfvrsn=c727183b_2)