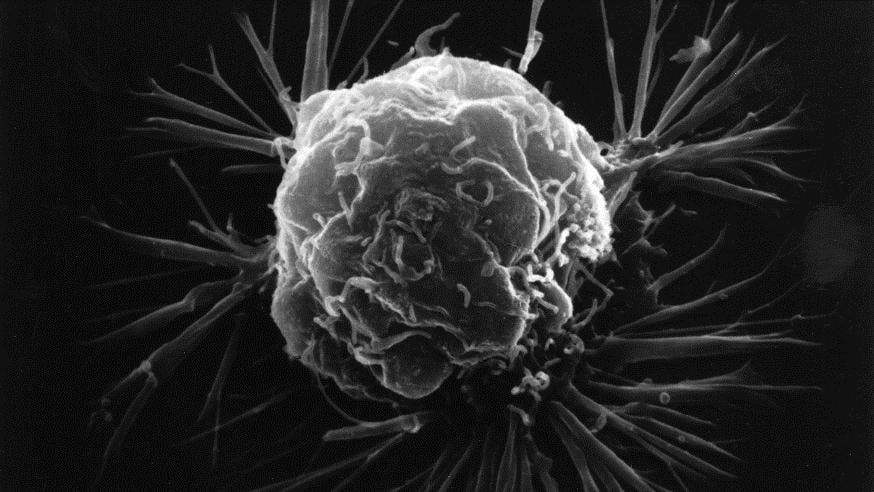

Breast cancer cell. Credit: National Cancer Institute

You might assume breast cancer is something that only really affects older women – and, to some extent, you’d be right. At least four out of five cases are in women over the age of 50.

While breast cancer in older women is clearly much more common, around 7% of the women diagnosed with breast cancer are under 40, when most women are still premenopausal. In fact, according to the Office for National Statistics, 42.4% of all cancers occurring in women aged 15-49 is breast cancer.

Tumours in younger women are generally more aggressive and found at a later stage, leading to lower survival rates. Their diagnosis comes at a time when many women are caring for young children and are in employment, resulting in significant impact on their psychological wellbeing.

Even when treated successfully, these women face the long-term effects of treatment, such as reduced fertility and early menopause. It’s clear that research to better understand the causes of premenopausal breast cancer, and improve diagnosis and treatment, is urgently needed.

But, there are challenges for researchers working in this field. I spoke with Dr Minouk Schoemaker, an epidemiologist at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, about how she’s part of a research collaboration that will hopefully help to improve knowledge in this field.

The research behind the disease

Dr Schoemaker’s work is mainly focused on the Breast Cancer Now Generations Study, a large, comprehensive scientific study of the causes of breast cancer conducted at the ICR, which includes over 110,000 women from the UK. She explained that a problem in research into premenopausal breast cancer is the relatively small number of cases compared to post-menopausal.

There are indications that some of the causes of breast cancer in premenopausal women are different from those for postmenopausal women. However, given that the rates of premenopausal breast cancer are comparatively low, there are fewer patients for researchers to study, and therefore our knowledge is more limited.

For example, specific breast cancer subtypes cannot often be examined in individual studies, despite the identification of these contributing factors being critical to prevention.

“Most prospective studies recruit women aged 45-50 onwards because breast cancer in more common in older women.

“We need to recruit younger women to allow for more research into premenopausal breast cancer, but this is often a funding issue because high-quality cohort studies require a large number of participants followed up over long periods of time”, says Dr Schoemaker.

Statistically speaking

According to Cancer Research UK, the survival rate of breast cancer in women aged 60-69 is 92% over five years but for women aged 15-39, it is around 85%. On top of this, in women diagnosed at a more advanced stage the survival rate falls to 24%.

“Triple-negative (TNBC) is more common in younger, premenopausal women than in older women, which in itself is more aggressive and harder to treat than other subtypes. But also young women diagnosed with breast cancer are more likely to have an inherited genetic predisposition for breast cancer, for example mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, than older women.”

The reality of diagnosis

Lauren Tedaldi is in her mid-30s and comes from a family with a history of breast cancer. As a teenager she was warned about her increased risk of breast cancer, after two aunts died from the disease.

However, it was not until she was older that her parents sat her down, told her that her cousins, as well as her dad, had been found to be carriers of the BRCA1 mutation. She decided to get tested just in case, going through the regular process of pre-testing counselling.

“Although counselling was good, I didn’t truly understand the mental impact of a positive result. I didn’t really believe I would have anything but a negative result.”

But when the results came back positive she recalls really struggling with the outcome, admitting that she couldn’t face it.

“I hid it. If I did try to talk I’d get too upset, so I just ignored it in company and only thought about it when I was alone.”

Help transform breast cancer research by supporting our new programme of research into hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

Read more

The limitations for patients

Lauren (pictured right) said one of the challenges she faced after her test results was the limited information available.

“The problem with breast cancer,” she explained “is that your outcomes can be really varied, depending on which subtype of breast cancer gene you have. I knew that having the BRCA1 mutation increased my risk of getting breast cancer, but there hasn’t been enough research done to tell you your exact risk.

“You just look for the biggest number. And this was true even after my cancer diagnosis – no one can really tell me what my chances of a second breast cancer are or what my chances of ovarian cancer are. Just that it’s pretty high.”

What the ICR is doing

In 2013, the ICR, teamed up with the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) to form the Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative Group in an effort to identify the factors contributing to premenopausal cancer.

Working as part of the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium, which includes over 50 high-quality cohort studies and more than 7 million individuals, the Collaborative Group is working to pool current data to enable large-scale studies into premenopausal breast cancer and the associated risk factors.

This collaboration allows Minouk and her colleagues at the ICR and NIEHS to gain access to much more data about younger women with breast cancer, enabling them to explore risk factors in more detail than is possible in individual studies.

Investigating the risk factors

Dr Schoemaker hopes that by pooling the data the Collaborative Group has access to, they will gain a better understanding of the associations and risk factors identified in previous studies, such as the association of breast cancer risk with body size/BMI and weight gain, or the effect of physical activity, a modifiable factor, which could eventually help inform women how much, how often and what type of exercise to do to reduce their risk of developing premenopausal breast cancer.

Pregnancy is also associated with premenopausal breast cancer and is known to have a “dual effect” on breast cancer risk. After childbirth there is a short-term increase in the risk of breast cancer, followed by a long-term protective effect.

Although previous studies have shown a 1.25- to 3-fold increase in the risk of breast cancer for up to 10 years post-childbirth, the magnitude of this varies across studies and the influence of age, oral contraceptive use, breastfeeding, family history or cancer subtype remains unclear.

Lauren’s surprise

Given her family history and genetic test results, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust referred Lauren to a screening programme, the first step of which was an MRI.

However, when tested to ensure she could be injected with the radioactive tracer, she found out she was pregnant. All of a sudden, Lauren had a purpose, a focus other than her test results, and this is what helped her move on with her life.

“I didn’t really have a choice,” Lauren pointed out, “Had I found out I had cancer before I got pregnant, my husband and I probably wouldn’t have tried for children at that point, but I’m not sure they would have even found anything had I had the MRI – we’ll just never know.

“At that time in my life, we’d decided to continue to try for a baby as I thought, even if I had the faulty gene, it wasn’t supposed to manifest until I was over the age of 40.”

For Lauren, having her daughter Milla was a blessing and all seemed well until, at around 6 months, she realised something was wrong.

“After about a week into weaning Milla off breastfeeding, one part of my right breast was still feeling weird. I couldn’t lie on my front, and the worry that it was cancer was always at the back of my mind”.

On the fast track for treatment

When Lauren went to doctors she was immediately fast-tracked for biopsy due to her family history. It turned out she had a 5cm cancerous tumour and was given the option of having chemo or going for a mastectomy. This was obviously a shock but she has nothing but praise for Guy’s and St Thomas’ after the support she received.

“I wasn’t rushed and every question I had was answered. They explained that chemo treats the whole body, whilst surgery treats the direct tumour location.” Lauren explained that she was scared of chemo, of losing her hair and of the effect it would have on her body.

“People don’t know what to say when they know you have cancer, and I didn’t know what to expect, so I ended up closing off from people.”

She described how people used to tell her that she looked great, which she felt put pressure on her to always look well, and how she was told she was ‘brave’ and ‘inspirational’, when she didn’t want to be either of those things. “Brave is a choice,” she explained, “I didn’t have a choice – I couldn’t have given up.”

In the end, Lauren underwent chemotherapy first, followed by a double mastectomy to reduce her risk to about 5% and when I asked if she felt aware of the difference in age between her and other patients she told me: “I was definitely the youngest person in chemo, it was a mixed cancer ward so there were all sorts of people there.”

“But I wasn’t really there to chat, I just wanted to get there and get it done. I prepared in advance as a coping tactic, with my TV shows and jumpers, but as a new mum it was also some much-needed ‘me’ time.”

However, in the breast cancer surgery bay she saw the difference in age, with all older women who weren’t always that sensitive and would tell her to ‘be positive’ and that she ‘might have more kids’, without really understanding the implications of what they were saying.

Looking to the future

With the Collaborative Group focused on young women, Dr Schoemaker hopes to address some of the open questions around premenopausal breast cancer, increasing our knowledge about the causes and hopefully aiding prevention.

Looking back on the last year, Lauren is now technically breast cancer free – but she explained to me that she doesn’t think she’ll ever feel truly free of breast cancer.

“I feel like I have less time to waste – in meetings, at work, at home, walking along the street. I won’t know how this experience has changed me for years but when I look at photos of myself before the cancer I think, ‘that person didn’t know what was coming’. But then my daughter came at the same time, so it’s hard to know what changed me, the baby or the cancer. Probably both.”

The Breast Cancer Now Generations Study is funded by the generous support of M&S, The Doris Field Charitable Trust and the Liz and Terry Bramall Foundation.

comments powered by