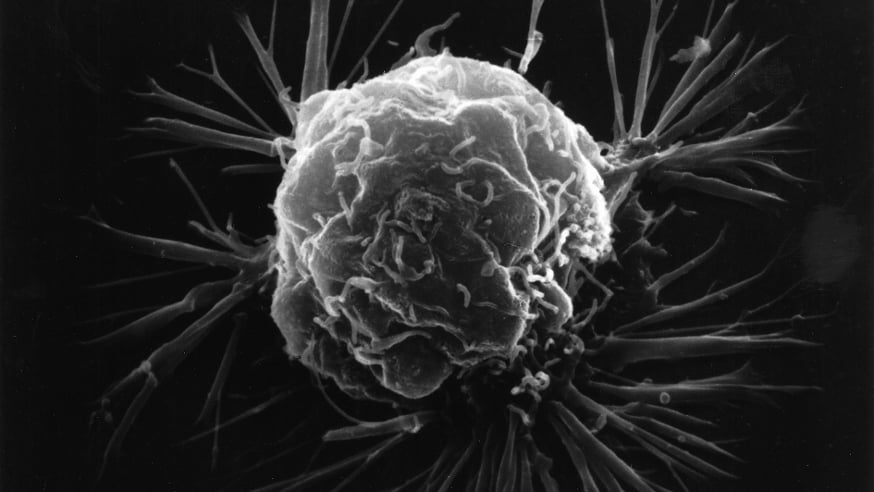

A breast cancer cell (photo: National Cancer Institute)

This week, many UK newspapers led on news that researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and the Universities of Manchester and Birmingham had shown a combination of two drugs to be unexpectedly effective at treating some breast cancer patients.

The results of the clinical trial were revealed at the European Breast Cancer Conference in Amsterdam on Thursday 10 March 2016.

The findings caught the media’s attention because the effect of the treatment was so rapid and dramatic in some patients. As Professor Judith Bliss, Director of the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the ICR and who led the trial, described in The Daily Telegraph: “Our study, which was funded by Cancer Research UK, was designed to see which patients showed early response from a biological point of view if they were given Herceptin, Tyverb or the combination of the two drugs.

“We wanted to use the short ‘window' between a patient being diagnosed and surgery two weeks’ later to examine the effects of the drugs whilst the tumour could still be sampled to see how it was responding.

“In the combination group it quickly became apparent that some patients had a dramatic response in their tumours. In about one quarter of cases, patients had either no invasive tumour left by the time surgeons operated or only a very small amount of invasive tumour left.”

Many diseases

Breast cancer is not one disease - it is thought there are many different types all with their own molecular signatures.

The drugs tested in this trial were targeted at a particular type of the disease, known as HER2-positive breast cancer – and patients taking part in the trial had newly diagnosed disease which had not spread beyond the breast and armpit. Around 10-15% of the 53,400 women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer each year in the UK are characterised as having HER2-positive cancer.

Researchers wanted to pay a special tribute to the patients who took part in this trial and allowed them to make this finding, as Professor Bliss describes: “Our research is wholly dependent on patients who take part in our trials, we are so grateful to the those women who kindly agreed to join this research project at the time of their diagnosis, which was clearly a challenging time of their lives.”

Although there are already effective treatments for this type of cancer, and a complete response is common after three to four months of treatment, particularly when given another therapy alongside cytotoxic chemotherapy, the researchers said observing a disease response after 11 days with this drug combination was very surprising.

More work to do

This is exciting news and researchers were both surprised and delighted by the findings. It is important to consider, however, what happens next and what has still to be done before this treatment regime is offered to patients.

This data was presented at a scientific conference; the next step will be for the researchers to write up their results into a paper that will be subject to academic scrutiny. In a process called peer review, other knowledgeable academics will look closely at the research and check it is up to standard.

Then there will need to be further clinical trials that replicate this finding and look at the long-term impact of the treatment. These studies will also have to be evaluated and peer reviewed. Researchers will also want to figure out what it is that makes these two drugs work so effectively together, understanding their action might help them find other successful treatment combinations.

Professor Bliss says: “Seeing this response from patients is very encouraging: we hope this could be an effective treatment option in future. We are also intrigued by what is happening biologically – we would like to know why these two drugs seem to have such an effect together.”

The treatment will also have to be shown to be better than existing treatments. “We have gained so much over the last 10 years in improving disease outcomes, mainly due to routinely giving patients a year course of trastuzumab,” Professor Bliss explained. “Before offering the new drug combination, we need to be clear that any tailoring of treatment does not take a backward step in ‘losing’ any of the benefit that has been gained.”

So while cancer researchers are cautiously optimistic that this finding could provide a new way of treating women diagnosed with HER2 breast cancer in future, much more needs to happen before this treatment is offered routinely in the clinic.

comments powered by