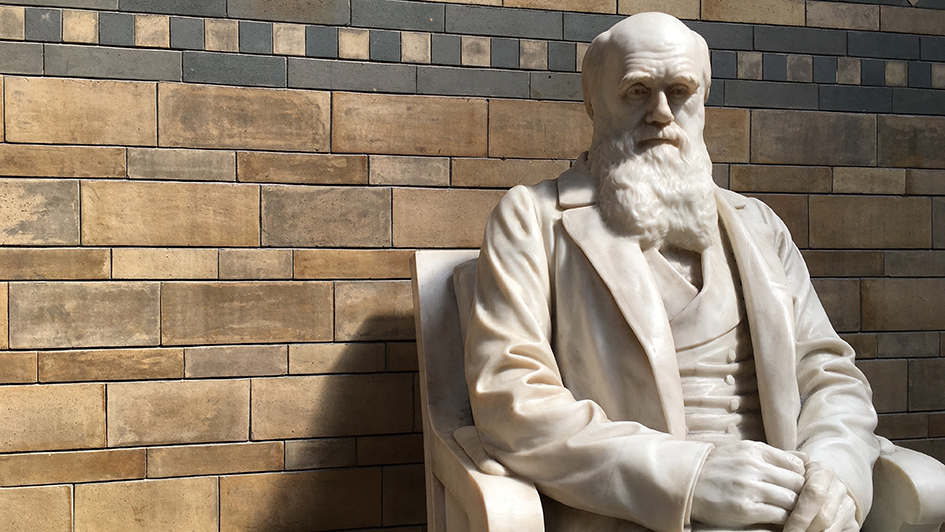

Image: Statue of Charles Darwin at Natural History Museum in London

Scientists in our Centre for Cancer and Evolution here at The Institute of Cancer Research are working hard to better understand – from an evolutionary perspective – how cancer develops, changes over time and can become resistant to treatment.

Cancer drug resistance is one of the greatest challenges to successful treatment. Researchers right across the ICR are working on ways to tackle cancer evolution, from liquid biopsies to detect drug resistance early, to artificial intelligence tools to predict how cancers will evolve and spread.

Cancer plays by its own rules

In honour of Charles Darwin’s 210th birthday, Professor Mel Greaves has invited self-proclaimed ‘arch-Darwinist’ Professor Joel S. Brown of the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida, USA, to give the annual ICR Darwin Lecture, where he will share with us his approach to cancer as a player in an evolutionary game.

A game, Professor Brown told me, can be defined as any situation in which the best strategy of each ‘player’ depends on the strategies of others. When healthy cells become cancerous, they go rogue and start playing by their own rules, becoming their own player in an evolutionary game.

But unlike in classic game theory, which you might be familiar with through the work of John Nash or know from his biopic “A Beautiful Mind”, cancer can’t make rational decisions – its strategies are governed by Darwin’s principles of natural selection.

Survival of the fittest

“Cancer cells evolve adaptations in response to their tumour ecosystem that in some ways can be dazzlingly fascinating even as they are horrific in their consequences for the patient,” Professor Brown explained. It’s a classic example of survival of the fittest.

“They evolve adaptations for rapid growth, to be able to use resources efficiently in an extremely limited environment, to evade the immune system, and in response to each other.”

There’s one evolutionary pressure that cancer responds to which researchers here at the ICR are particularly concerned with, and which forms a key part of our research strategy – its ability to evolve to in response to treatment.

The ICR's Centre for Evolution and Cancer is led by Professor Mel Greaves and aims to apply Charles Darwin’s principle of natural selection to our understanding of why we develop cancer and why it is so difficult to treat.

Read more

Staying one step ahead

In this age of personalised medicine, researchers have developed ways of treating cancer that is increasingly tailored to individual people’s tumours, and the specific genetic changes within the tumour.

But according to Professor Brown, perhaps the current focus in cancer treatment is too much on personalising medicine at one particular point in treatment. By putting all our efforts in treating the cancer at that time, we miss out on the opportunity to plan ahead for the inevitable changes in the cancer. That way, we risk losing our edge.

Changing from followers to leaders

“If a treatment stops working for a patient and their cancer comes back we change strategy, but the game has been won or lost way earlier. We start out the leader, but in current therapy we quickly become the follower, and start having to chase the cancer.”

In terms of game theory, cancer treatment is a leader-follower game, similar to reverse psychology. If you already know that the cancer is going to evolve adaptations that will allow it to evade the treatment you are giving at the time, then you can plan ahead for the next step in the treatment.

Dr Andrea Sottoriva, one of the Team Leaders in our Centre for Cancer Evolution, agrees: “Like in a game of chess, the aim is anticipating the next move of the adversary, to ultimately win the game.”

Forward-looking approach

So how can evolutionary game theory help us defeat cancer? Professor Brown believes there are two main ways of applying it in the clinic.

Firstly, he calls for a more forward-looking approach using what he calls a ‘resistance management plan’, with clinicians starting to plan ahead well before there’s even a hint of a treatment stopping working and the cancer coming back.

Part of such a resistance plan, Professor Brown told me, could be a ‘kick ‘em when they’re down’ plan. “When the cancer becomes clinically undetectable or barely detectable, that’s when we want to pull out all the stops, and when we may want to have an even more personalised medicine.”

More than a game for cancer patients

Then, Professor Brown suggests we should get in the habit of delivering ‘therapeutic feints’, to push the cancer to commit to a particular evolutionary pathway.

“Chances are, when you give the first round of therapy based on personalised medicine, a lot of changes would happen in the first few weeks that we would not have been able to anticipate at the outset. Instead, we could give patients a drug for a few weeks, and then move on to personalised treatment.”

Ultimately, Professor Brown wants his work to make a difference for cancer patients and cancer care. “In cancer therapy, it’s patients’ lives, and quality of life, that’s at stake. There’s an evolutionary game going on – and cancer patients are the playing board. They’re the ones that live and die by it.”

comments powered by