Discovering and developing new targeted, personalised cancer drugs — which match to particular genetic mutations in tumours for each individual patient — has long been a cornerstone of the ICR’s strategy to defeat cancer.

In recent years, we’ve seen innovative targeted drugs significantly extend survival and improve quality of life for many adults with cancer.

But while adults have benefited from these new, smarter treatments, the development of targeted drugs for children has lagged well behind. We know less about the genetics and biology of cancer in children than we do for adults, and — in part because of this — it has been difficult to run clinical trials of new targeted therapies in kids.

The upshot is that the vast majority of children are still treated with conventional chemotherapy — despite the side-effects of treatment being particularly severe in kids, and often lasting throughout life.

It has been very frustrating that children have not benefited to the same degree as adults from the new wave of precision, molecularly targeted drugs. So we were delighted to launch a major new initiative in childhood cancer research yesterday with our hospital partner The Royal Marsden, which we hope will go some very considerable way to helping close this unacceptable gap.

A new horizon in personalised treatment

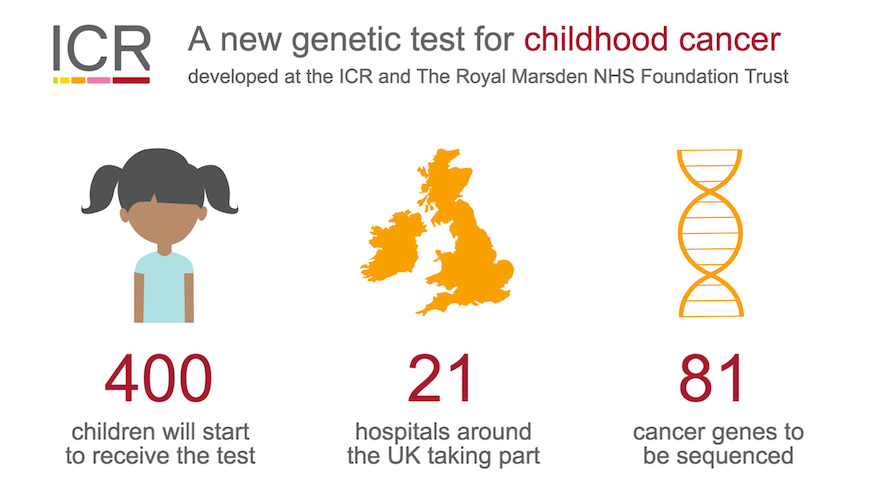

Researchers at the ICR and The Royal Marsden have developed a new genetic test that allows the sequencing of a series of important cancer genes — a panel of 81 genes in total by Next-Generation DNA sequencing — in children’s tumours.

The aim of the new research, which is led by Professor Louis Chesler and Dr David Gonzáles de Castro, is to routinely detect mutations in children’s tumours that could be targeted by personalised cancer drugs — potentially repurposing drugs that are already used to treat adults whose tumours have equivalent defects.

Around 400 children at 21 leading hospitals across the UK will now start to receive the test, the development of which was funded by the kids' cancer charity Christopher’s Smile.

It’s the first time a gene panel test will be made available to children and we expect that this initial pilot programme of clinical testing — which will take about two years and be funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR — will herald a wider rollout and routine use on the NHS in the future.

The test, which uses very small amounts of tissue that is already collected for conventional diagnosis, has already been shown to be robust and reproducible in the lab and this next phase of testing is aimed at evaluating its reliability and usefulness in the clinical setting. If this clinical pilot stage is successful it should open up a new horizon in personalised treatment for children’s cancer with young patients eventually being routinely matched to the most appropriate approved drug, or directing them to an suitable clinical trial of targeted therapy, according to the results of the genetic test.

And where no approved drug or trial agent is available, clinicians could make the case for a particular treatment, for example on a compassionate use or ‘named-patient basis’. In such cases it would be important for the results of both the genetic test and the clinical response to be carefully documented and captured in a database so that the learning is shared and can be built upon.

Better responses, kinder drugs

This new test opens up the exciting possibility of therapeutic responses in children that we already see with targeted therapies in adult patients — or even greater successes. Another major benefit is that the use of targeted treatments could spare these young patients from the damaging side-effects of chemotherapy.

Some 80 per cent of children under the age of 14 years are already cured of cancer. But 20 per cent are not and survival is much worse in some subsets of cancers. Furthermore, of those who do survive, a very large number suffer from long term side-effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy — such as damage to the brain, lung, heart and muscles, as well as impairment of physical growth and intellectual development. In addition, the induction of second cancers is also a real problem.

The side-effects of chemo and radiotherapy are more severe in young children because they are still growing and developing, and so their organs are more susceptible to damage.

The urgent need for kinder treatments was highlighted yesterday morning on BBC News by Jack Daly, a teenager whose successful treatment for cancer has had long-term effects. Jack and his mum Helen are brave to share their personal experiences and are an inspiration to those of us working in cancer research.

So too are Kevin and Karen Capel – the founders of the Christopher’s Smile charity – who lost their son Christopher to a medulloblastoma brain tumour, just nine days before his sixth birthday and after a gruelling course of treatment. Since then the Capels have been tireless campaigners for targeted therapies for kids with cancer and strong supporters of research and the ICR.

A great example of how the new approach can work was shown in the BBC Panorama broadcast last year about the bench-to-bedside research on the discovery and development of new drugs at the ICR and the Royal Marsden. In the programme, we saw a young patient Sophie responding very dramatically, and with no significant side-effects, to a targeted drug (an ALK inhibitor) that had in fact been developed to treat a subset of adult lung cancers with mutations in the ALK cancer gene. Sophie was given the drug because gene testing showed that her tumour also had an ALK mutation that was a likely driver for her own disease.

We also know that some children’s cancers have mutations in the BRAF cancer gene and so we can imagine treating such young patients with BRAF inhibitor drugs that are already approved for adult melanoma skin cancer.

The future

My strong hope is that making this new gene test available will help to encourage pharmaceutical companies to carry out more trials in children.

At the moment there are significant regulatory and financial barriers to developing new treatments for childhood cancer, and there simply are not enough trials being run.

This new gene test developed at the ICR and the Royal Marsden will encourage companies to carry out more trials in kids with cancer, because it will be made readily available at a reasonable cost — around £200 per test. It could, we hope, lead to new partnerships with companies for the ICR and others, which can help in the delivery of more new trials for childhood cancer.

At the ICR we will continue to call for changes to be made to the current system of cancer drug development, which is fundamentally flawed when it comes to bringing through new drugs for all types of cancer but is particularly problematic for young cancer patients — which is just not acceptable.

We want to see policy changes that could improve the provision of innovative new drugs to all patients on the NHS, as well as specific changes to rules that govern how childhood cancer trials are carried out.

Cancer can be a devastating diagnosis at any age — but to me, and I know many others, there is something especially cruel about cancer in young people, infants and even babies. We only have to look at our own families and friends to imagine how painful this experience must be for those affected. And having talked to many parents who have lost young children to cancer I am so impressed by their resilience and determination to help us.

The good news is that now is a really exciting time for childhood cancer research, as the passion of researchers and of our fantastic supporters leads to a better understanding of the genetics and biology of kids cancers — which will result in more effective and kinder treatments. And will in turn lead to longer survival with higher quality of life.

The development of this new genetic test is one such advance, and should help to widen access to a new generation of new smarter, kinder treatments for children with cancer.

comments powered by