The UK’s biggest annual cancer research conference – the NCRI – is not the only one drawing our scientists this weekend. As the talks start on Sunday in Liverpool, some of our researchers will be making an alternative trip over to Berlin for ‘Goodbye Flat Biology’ – with more than 250 delegates, the biggest conference to date to focus on creating tumour models from cells in three dimensions.

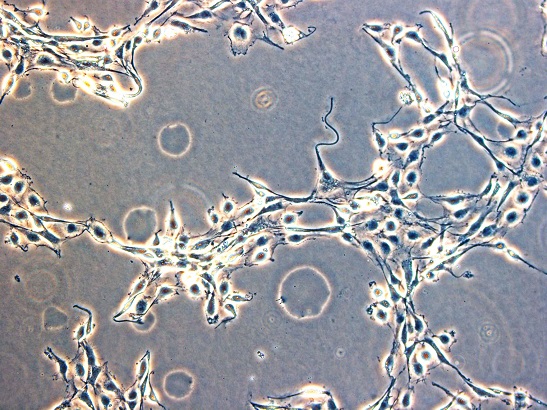

‘Two dimensional’ cell cultures – the well-known research model of cells grown in a flat sheets in plastic dishes – can tell researchers a lot about cancer, but only replicate the disease up to a point. Tumours, particularly advanced tumours, are three-dimensional structures made up of different cell types, with their own blood supply and a complex relationship with the non-cancerous tissues surrounding them.

The things that make tumours metastatic – that help them invade and spread around the body, colonise new sites and cause the majority of cancer deaths – are particularly difficult to mimic in a petri dish. Researchers need new, three-dimensional tools to study them.

That’s what researchers at the ICR, including Professor Sue Eccles and Dr Maria Vinci – who are co-chairing the conference – are developing. At the conference, one of a series in specific research areas run by the European Association for Cancer Research, delegates will share knowledge and expertise in this exciting emerging field.

Animal alternatives

These new 3D models will become important research tools in their own right – but they are also an example of how cancer researchers are aiming to reduce the number of animals used in preclinical research.

Although earlier-stage studies of cancer can rely on cells in a dish, ‘2D’ cell cultures cannot reliably mimic how cancers behave inside a body – such as cancer cells’ ability to move and invade tissues. Scientists often need to look in mice to see how they behave in a living organism – our researchers, for instance, often use mice to see whether a potential drug has an effect on a living tumour. The expectation is that 3D models will take the place of mice for some of this sort of work.

Professor Eccles’s own 3D cell cultures have already reduced the number of mice needed to bring each new drug to the clinic – as she discussed at the British Science Festival last year at a session arranged by the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research. The NC3Rs, the leading national scientific body dedicated to these goals, has funded some of our work to develop new 3D models of cancer.

comments powered by