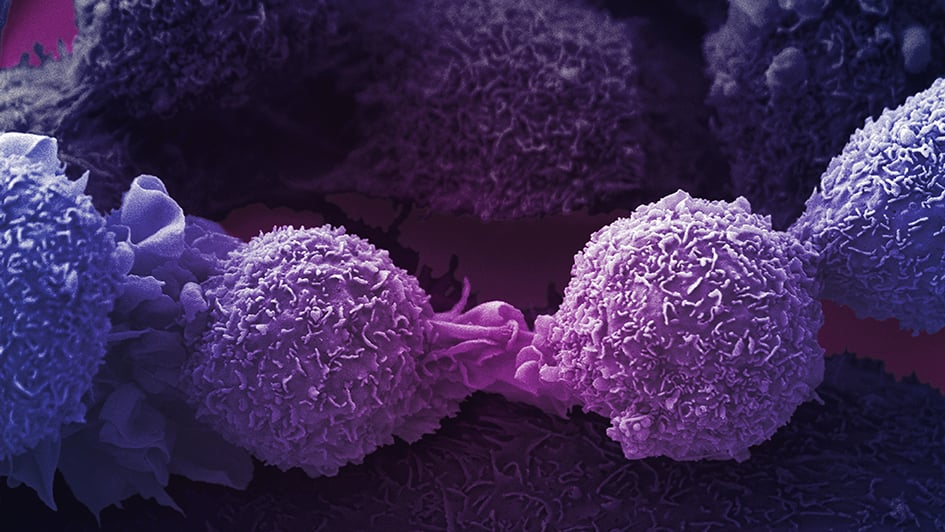

Image: Lung cancer cells. Credit: Anne Weston, Francis Crick Institute. CC BY-NC 4.0

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death in the UK and globally. As there are usually no signs or symptoms in the early stages, it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage and consequently, outcomes for patients can be poor. Additionally, the risk of a tumour coming back after surgery is high even if the cancer is diagnosed early. Studies have shown that complementary treatments, such as targeted therapies, can reduce this risk.

Dr Paul Huang is Leader of the Molecular and Systems Oncology team at The Institute of Cancer Research. Focusing on lung cancer and sarcoma, the team aims to understand why tumours develop resistance to drugs, and to find new ways to treat patients whose tumours come back after treatment. Paul has contributed to a new white paper, published in a Nature supplement for Lung Cancer Awareness Month, on a type of lung cancer known as non-small cell lung cancer.

The white paper discusses how targeted treatments have revolutionised patient care in non-small cell lung cancer. Targeted drugs work by targeting specific genes and proteins that are involved in the growth and survival of cancer cells.

“Lung cancer is one of the most common types of cancer, and there is hope in terms of precision medicine, that we can match people’s mutations to specific targeted drugs that will target their cancer effectively. These drugs allow us to control the disease and shrink the tumour,” Paul explained.

Targeted therapies block activity of proteins

For example, EGFR inhibitors target and block the activity of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR). These are proteins which, in normal cells, are involved in pathways that control cell division.

Cancer-causing mutations commonly occur in the EGFR gene in non-small cell lung cancer. If a mutation is present in the gene, this means the resulting EGFR protein, that is built using the gene’s instructions, will not work properly. This can result in uncontrolled cell division, which forms a tumour. EGFR inhibitors can be effective in blocking the activity of the abnormally functioning protein and slowing or stopping the tumour growth.

“Targeted therapies first came into play about 15 years ago,” said Paul. “Researchers sequenced patients' DNA and found that they did particularly well on certain drugs according to the specific mutations present in their tumours.”

Targeted drugs aimed at blocking the activity of the EGFR protein are used in combination with other treatments like radiotherapy, or surgery. However, the targeted treatments are only effective for a period of time, as gradually, tumours find ways to work around the effects of the drug, and the drug becomes increasingly less effective. There are currently three generations of EGFR inhibitors in use.

‘Whack-a-mole’ treatment strategy

“We can think about it like a ‘whack a mole’ strategy,” explained Paul. “The first generation of EGFR inhibitors holds the disease at bay for a period of time, after which the cancer develops resistance to the drug and the ‘mole’ pops back up, the cancer comes back and we have to change direction.”

The next generation of EGFR inhibitors were developed to target specific mutations acquired as a result of exposure to the first generation drugs. The ways in which tumours become resistant to the drugs are still being uncovered.

“At the moment, our understanding of the reasons why tumours become resistant to treatment is somewhat limited,” added Paul. “With first generation EGFR inhibitors, we understand about 70 per cent of the resistance mechanisms. For the second generation drugs, the figure is much lower - around 30-40 per cent. If a patient’s tumour comes back and we understand why, they can be treated with targeted drugs. If we don’t know the reason, the only line of attack is chemotherapy – which is likely to impact more heavily on a person’s quality of life.”

Each generation of EGFR inhibitor will work effectively for around 12-18 months, after which tumours develop resistance mechanisms, the drug stops working, and a new treatment must begin.

Common versus rare mutations

“We are in quite a unique situation with EGFR inhibitors. They are not new drugs per se, compared with immunotherapies, for example. So we have a lot of knowledge and experience treating patients with these drugs, and a good understanding of how they target the two most common mutations, which are present in about 80 per cent of non-small cell lung cancers. If you have one of these common mutations, there is a high chance that if you’re given the drug it will work,” Paul said.

“For those patients with mutations that are rarer, the same drugs will not be effective at treating their cancer and their prognosis will be much poorer. For these mutations, we are where we were 15 years ago for the more common mutations.”

A good example of a rare mutation is exon 20 insertion, where extra base pairs – the components that make up DNA – are inserted into the EGFR gene. This is present in only about 4 per cent of EGFR mutated tumours. Patients with this mutation do not respond well to the EGFR inhibitors that are already approved for use. Research is ongoing to develop new drugs which will be effective for patients with an exon 20 mutation.

Shifting the narrative

Because of the rise in resistance, and the resulting high likelihood of cancer coming back after treatment, there is a school of thought that attempts to shift the narrative away from focusing solely on getting rid of the cancer – often at the expense of the patient’s quality of life – and towards thinking about managing cancer as we do other long term health conditions like heart disease and diabetes.

“When I was on the ‘You, Me and the Big C’ podcast last year, I heard it described as ‘kicking the can down the road’. You’re trying to hold the disease at bay for as long as possible,” he said. “Of course, we should still aim for cures and this doesn’t diminish the ground-breaking work happening in cancer research at the moment. Immunotherapy gives a long term response with relapse unlikely, so oncologists are happy enough to say that patients are ‘cured’.”

“With EGFR inhibitors, the situation is very different and almost 100 per cent of patients get a relapse after the initial period of response to the drug. EGFR inhibitors can buy several years of time for a person where their disease is controlled. When the tumour inevitably relapses, options become more limited,” Paul said.

“In BCL-ABL driven blood cancers, fourth generation targeted treatments exist. If every generation buys 12-18 months of time, that’s around five years total. If you think about other long term diseases like heart disease and diabetes, cancer could evolve into one of these situations, where we are managing the disease rather than trying to eradicate it. We could shift the perspective to thinking about how people can live well with cancer, with the right set of medications to keep the disease at bay without debilitating side effects.”

‘Cancer might be a part of my life, but it’s not the end of it’

Angela Terry, aged 67, is a trustee of the patient support group EGFR Positive UK. She was diagnosed with stage 1 EGFR+ lung cancer in January 2019, while on a skiing trip in Austria. On her return to the UK, she underwent further tests and it was discovered that the cancer had spread to her spine.

Angela Terry, aged 67, is a trustee of the patient support group EGFR Positive UK. She was diagnosed with stage 1 EGFR+ lung cancer in January 2019, while on a skiing trip in Austria. On her return to the UK, she underwent further tests and it was discovered that the cancer had spread to her spine.

Angela said: “It was a real shock when I was first diagnosed as I was so healthy and I’d never smoked. When I found out the cancer had spread and it was stage 4, I remember asking my oncologist if it was going to kill me, and he said that yes, it probably would at some point.

Image: Angela Terry with her husband Robert and grandchild Matilda

"Cancer was all I could think about at that time – I’d lie in bed going over all the things I’d no longer get the chance to do, and all the things I’d miss out on that I’d always assumed I’d be here for.

“But I don’t think of cancer as a death sentence now. I’ve been on a targeted treatment called afatinib for the last 14 months, and I’m doing so well I honestly feel like a fraud. I can do most of the things I want, I don’t experience any daily pain, I can manage my side effects and my quality of life is really high. My oncologist told me to look at cancer as a chronic disease and that’s really helped me to stay positive. I know therapies only last so long, but there’s no point worrying about that. If my cancer does become resistant to afatinib, I hope there will be other treatments for me to try – and in the meantime I just want to enjoy life to the full.

“Six months ago, my daughter gave birth to my first grandchild. Thanks to my treatment, that’s six months I’ve had to get to know her and hold her (when coronavirus restrictions have allowed). Cancer might be part of my life, but it’s not the end of it.”

Future opportunities

Research is developing at a rapid pace. It is very possible that people who are beginning targeted treatment now will find they have additional treatment options further down the line as new drugs are developed.

“I am optimistic about the future,” Paul said. “This is a very active area of research. Understanding is improving, we now know more about tumour genetics, and cancers’ ability to evolve. Fundamentally it boils down to increasing understanding – work is ongoing to try to better understand disease evolution and drug resistance mechanisms.

“EGFR inhibitors have given us better ways of managing lung cancer, and there are other new treatments on the horizon. One positive step is that we can now use DNA circulating in the blood to analyse tumours, whereas before the only way to do this would be a very invasive procedure to take a biopsy from the tumour in the lung. Development of new drugs means we can switch therapy if the tumour burden starts to increase. We have options.”

People with cancers of unmet need urgently require new treatment options to help them survive their disease. Improving the outlook for these patients is one of our key fundraising priorities and philanthropy plays a key role in our progress.

Find out more

comments powered by